(Click any of the images to zoom in on them.)

Drabble is one of the strips that are usually in the middle of the newspaper page, easy for the eye to skip over. It’s the very definition of “eminently forgettable.” I’m fairly certain that if there wasn’t a picture of the main character right above this paragraph, you’d have no idea what comic I’m talking about. In fact, you still may not. If that’s the case, then just keep reading as a favor to me — I’ll take all the charity I can get.

Drabble is the creation of Kevin Fagan, a man who has never held a job that did not involve creating Drabble. In 1979, Fagan became the youngest comic-strip creator to be signed to a syndication deal (United Feature Syndicate). He was 21, and had four years of college-newspaper cartooning under his belt. Drabble was borne from Fagan’s desire to “do a strip that students could relate to. I wanted to avoid political stuff, because that’s what every other college cartoonist does.”

Thus we’re gifted with the story of dimwitted Norman Drabble, his dimwitted father Ralph, and their family that’s not really important enough to mention (precocious Patrick, precocious Penny, mom June/Honeybunch, Oogie the cat, Wally the weiner dog, and Bob the duck, as well as sarcastic Norman’s-love-interest Wendy, if you must know). Like The Simpsons, Drabble has, over the course of its run, drifted away from focusing on the son and more towards focusing on the father, perhaps due to the shift in Fagan’s perspective as he ages.

Let me make one thing clear: Drabble is not the worst comic in the newspaper. (That honor goes to Momma.) About once a month or so, it achieves the base level of quality that, in a perfect world, would be the minimum acceptable standard for all syndicated comic strips. And, from all accounts, Kevin Fagan is a helluva nice guy.

That being said…

Drabble is retarded. It’s every cliché from every sitcom ever made. This week is Week Two of a massive story arc involving Norman’s struggle with a tip jar — territory that was a C-plot in a Seinfeld episode from ten years ago. Drabble has mined such comedic veins as math (pi r squared = pie is round!), travel (New York taxicabs drive crazy!), and if you’ve ever not laughed at a joke because it was too dumb or obvious, Kevin Fagan will make it into a Drabble strip in 2015.

The characters are cliché. Ralph (the dad) is Homer Simpson without the interesting antics, repeatable catchphrases or pitiable quirks. Norman (the older son) is just dumb in a shallow-fiction way, meaning that at every juncture you can predict that he will make the really obvious wrong decision. Because he’s dumb, you see! I’d love to see a comic strip about a realistically dumb kid, who’s always making bad choices because he gets angry too much and likes to spite those who think they know better than him, and who’s powerlessly watching his life spiral out of control while desperately trying to forestall the inevitable by turning to bad homemade meth and Red Hook and punching holes in walls while hopped up on aerosol paint fumes. I knew lots of those guys in high school, and any of them would be much more fascinating to watch than Norman from the detached distance of a comic strip:

Hypothetical situation: At a salad bar.

Norman: Sneezes at the sneeze shield. To the chagrin of onlookers, he explains: “Well, it’s a sneeze shield, isn’t it?”

Realistic dumb guy: Leans underneath the sneeze shield to get at the beets. Sneezes directly onto the salad at point-blank range. Looks around furtively, and amidst disapproving glares, he stalks off angrily, shouting, “I didn’t do nothing!” Brow furrowed, he is on the receiving end of silent stares and whispers for the rest of the night.

Here’s a Drabble strip from the family’s aforementioned trip to New York. This was published on August 22, 2005:

In the first panel, we see the outside of the “Big Apple Hotel”, which would place the scene in New York City, at 752 Fifth Avenue. While trying to find a picture of 752 Fifth Avenue in New York (where, according to Google, the real Big Apple Hotel is located), I learned that most of that block of Fifth is occupied by the Bergdorf Goodman department store. In other words, it would seem — and I’m no expert — that the Drabble family is lodging in a department store. It’s sort of like that commercial, where the people are arguing in their kitchen, and then it turns out they’re actually in Ikea? If we live in a world where that could happen, I suppose it’s reasonable to assume that the dumb Drabbles could make a similar mistake. It should be said that I have never actually been to New York.

In the panel, someone (Ralph, probably) is saying, “The key to a successful visit to New York is to not look like tourists!” Right off the bat, you know where this is going. It’s so painfully obvious that this conceit was old when Bob Hope did it in his 1851 hit, Road to Antarctica. It’s so painfully obvious that I actually wrote this comic strip at the age of seven during Sustained Silent Reading in Mrs. Havens’ second grade class. It’s so painfully obvious that cave paintings featuring this same joke have recently been unearthed in France. Please, Kevin Fagan, give us a twist! Reverse our expectations! Do something that would actually meet the definition of the word “humor”! Perhaps, against all odds, he will: let’s read on.

In the second panel, Ralph is briefing the family on his plan to help them blend in. Norman and Honeybunch are smiling eagerly; Patrick and Penny are too short to have readable expressions. Ralph: “So I went out and bought some things that will help us look like native New Yorkers!”

Kevin Fagan, this is an open message to you: As I retype your dialogue, I find myself unconsciously changing it to make it shorter, more concise, and more interesting. Then I have to go back and correct it so it’s an accurate transcription. Please call me.

In the third panel, we see the (inevitable) punch line: Everyone’s dressed like tourists! Whoa-ho-ho! Boy, Ralph, what a dummy you are! Patrick is the moral compass, so to speak: “Are you sure native New Yorkers wear Statue of Liberty hats?” Norman’s not so sure, but Ralph is quick with the response: “Trust me! We’ll fit right in!” And the kicker: Mom and Penny roll their eyes! Whoa-ho-ho!

Before I delve further into the specifics of this particular strip, I’d like to offer Mr. Fagan a general note of advice. In many of his storylines — such as this week in New York, or the prior week in Niagara Falls, both part of a larger “vacation” story arc — he makes several weak jokes and then flees the scene, like a drive-by shooter peppering a house with random, hopscotch-girl-hitting bullets rather than hammering one humorous concept further home over several days, like a hit man stalking through a house and methodically shooting each occupant in the head, two bullets in the temple, then stripping off his surgical gloves and leaving them to melt in the fireplace. My recommendation is to play out certain situations in greater detail; to mine them deeper for comedy, instead of strip-mining the already-picked-over surface. If I try hard, like a horse pulling a heavy cart, I might be able to get a few more metaphors into this sentence, like a series of successively fatter men cramming their way into an elevator. In a library.

For example, here’s another of the New York series, this one printed on August 26:

Okay, I’m not going to retype all the dialogue, but you get the point: fish-out-of-water comedy. Ralph is a mall security guard, you see, so he feels it’s within his domain to perform a citizen’s arrest on some errant jaywalkers (never mind that jaywalking is a citation misdemeanor at best, and if they’re crossing at the crosswalk that’s probably more than good enough for local law enforcement. Apparently, New York has a big crossing-in-the-middle-of-the-street problem. I have never been to New York).

At the risk of giving Fagan too much credit, this strip has potential. It’s no knee-slapper, but it’s a prime example of a not-that-funny strip that’s tolerated because it’s the setup for the following week’s worth of storyline, each episode more hilarious than the last.

Unfortunately, this is not the case. The next day, Ralph has moved on to the Empire State Building — presumably he’s collared the wayward criminals and moved on with his vacation. The “citizen’s arrest” comic would have been a great setup for a few more days’ worth of Ralph attempting to catch the jaywalkers. His braggadocio in panels three and four, above, is a more productive use of his character than any sort of lovable buffoonery.

Besides, the more general the jokes, the shallower the humor — specificity is better. Not to draw this unfavorable comparison again, but when Homer Simpson came to New York, he spent the whole episode dealing with a parking ticket.

The tip-jar storyline, midway through Week Two as of this writing, is a good example of a concept when “longer” — more strips on a specific subject, like I’m advocating above — is not always “better”. It’s a matter of being more judicious with which concepts merit further development.

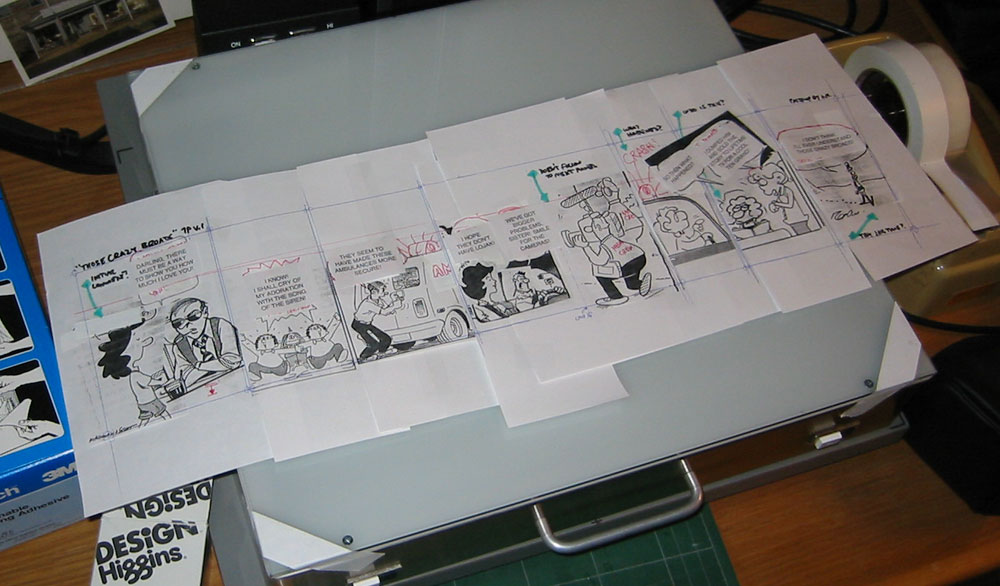

Setting aside the larger issue of the New York storyline, if we are to rescue the “dress like tourists” strip, we’ve got our work cut out for us. Fagan’s not that great of an artist, and he’s certainly not a very precise draftsman, but he’s given us a fair amount of specificity in the drawings that we’ll have to work around. Here’s my take on how to improve Drabble:

Until next time… I’ll see you in the funny papers.

— August, 2005