The creation of a comic strip is an arduous and seldom-rewarding task. Sweat, blood, tears, ink and occasionally urine must combine in a subtle alchemy on the illustrative page, by necessity ripping creative gashes in the artist’s soul that only sting more greatly with the acrid tang of exposure to the public consciousness.

The creators of The Wizard of Id, comic-strip greybeards Peter Parker and Bret “Hitman” Hart, once stated that the creative process “…is a [mistress]…with [cruel proclivities]…and a [sadistic streak]…that [only] sometimes leads to [the expected release; that of] an [attentive readership]…much less [widespread commercial appeal].” It’s a harsh world for a newbie to come to terms with; however, here at Wondermark we have streamlined this delicate and psychically dangerous process into a slick, successful art.

This does not mean that the processes described below are not difficult or torturous. They are both, in roughly equal quantities, sprinkled liberally with despair and occasionally garnished with a dash of coppery, nutmeg Hate. The following account will be by nature incomplete and imprecise, but it is our devout hope that some if not both of Wondermark’s devout readers will forgive the omissions, fill in the gaps, sit back, and learn a little something about comedy.

I. THE CONCEPT

Every step in the process is difficult, but coming up with the concept is by far the most emotionally taxing. Our creative staff reads several newspapers every day, staying abreast of current events both domestic and international, momentous and mundane, searching for those small items that — to the trained eye — represent the ever-changing character of the culture.

For example, recently in Italy a love-struck lunatic stole an ambulance and careened through city streets, wailing the siren to serenade his (hopefully impressed) bella. While this might rapidly become fodder for an E! Original Movie, it has to pass through a much more rigorous gauntlet of inquiry before being considered to be potential Wondermark material:

Is the subject riding the Zeitgeist like a tidal wave?

Our research department took an informal survey of 10,032 Americans and Western Europeans, asking them a variety of questions including their emotional reaction to this news item. The survey also included “dummy” questions designed to disguise the true nature of the survey, so as to weed out “prampters”, or respondents who concoct bogus answers for sport (“prampting”).

The dummy questions included such irrelevant gems as “What criteria do you use when deciding which brand of mung beans to purchase?” and “Did ‘moral values’ play a role in deciding who you would vote for in the Presidential election?”

The survey clearly indicated that the public would be highly receptive to us shining our blinding cultural spotlight on the Italian incident. This is the preeminent criterion for subject selection.

Is there sufficient material to inform a one-to-seven-panel, 3” x 9” sequential illustration?

Drawn out to its full potential, the paramour-turned-paramedic scenario could probably fill at least three panels (assuming the conventional setup-reinforcement-reversal paradigm), or, failing that, could possibly work as an extended single-panel non sequitur.

Would the proposed subject provide an opportunity for side-splitting humor, wry irony, clever witticism, or at the very least a Ziggyesque rhetorical observation?

This is the toughest question to answer. Sure, the material’s there, but is it worth doing? The reality was no, but for this exclusive look behind the scenes at the Internet’s first and only comic strip, we’ve made a special exception. For the sake of this article, we’ll be expending all the normal resources in the service of a doomed concept. This only differs from the norm in that we usually don’t recognize a concept’s stupidity until much later in the process, after it’s far too late (and too embarrassing, not to mention expensive) to turn back.

II. THE PROPOSALS

Once the concept is decided upon, a battery of scripts are written to create a comprehensive campaign. The writing staff, under the guidance of the Creative Director, will each write several “spec” scripts for consideration, approaching the concept from many different angles. For example:

WONDERMARK SPEC SCRIPT - “MAMMA MIA”

PANEL 1: A dapper YOUNG MAN kneels in front of a LOVELY LASS.

YOUNG MAN

There is nothing new under the sun,

save thy tender mercies. I shall

issue a dulcet cry to the heavens

befitting thee, o goddess of beauty!

PANEL 2: The Young Man leaps into a passing ambulance, knocking the previous occupant (a NECK-BRACED HOBO) into a canal.

YOUNG MAN

For thee, my dearest, there is

no muting the song of the swan...

PANEL 3: The Lovely Lass throws a hand to her forehead.

LOVELY LASS

Your promises are promising, my

promised one, but only by hearing

them amplified by the life-van’s

golden throat shall I be truly

convinced of your sincerity!

NECK-BRACED HOBO

Agkkk.

This script has a lot going for it; it’s got romance, passion, and the clever last-word-in-the-last-panel twist that always tickles the kids. But it’s a little heavy-handed for Middle America. In contrast, the script on the following page has our most discerning demographic firmly in mind:

WONDERMARK SPEC SCRIPT - “SNOWBOARD MONKEYS”

PANEL 1: A PIZZA CHEF tosses a disk of dough into the air. Suddenly, the WALL BREAKS IN!

PIZZA CHEF

Holy a-baloney!

PANEL 2: Three HIP BLACK CHICKS burst through the hole in the wall!

AFROED CHICK

What’s shaking, white meat?

HOOP-EARRINGED SISTA

Looks like his belly!

RESPECTABLE AFRICAN-

AMERICAN PROFESSIONAL

Bwah, ha, ha!

PANEL 3: The Pizza Chef juggles meatballs. An AMBULANCE races to the scene.

PIZZA CHEF

Looks a-like you a-gotta my number, eh!

HOOP-EARRINGED SISTA

Mm-hmm!

The writers and the Creative Director will further refine the campaign of scripts, finally sending a package proposal to the Executive Vice-President. The Executive V. P. will mull over the proposal, considering the resarch numbers and survey results and determining the best course of action. After much tinkering based on her own preferences and those assumed for the target demographic, she will approve a handful of scripts to be produced.

III. SPEC STRIPS

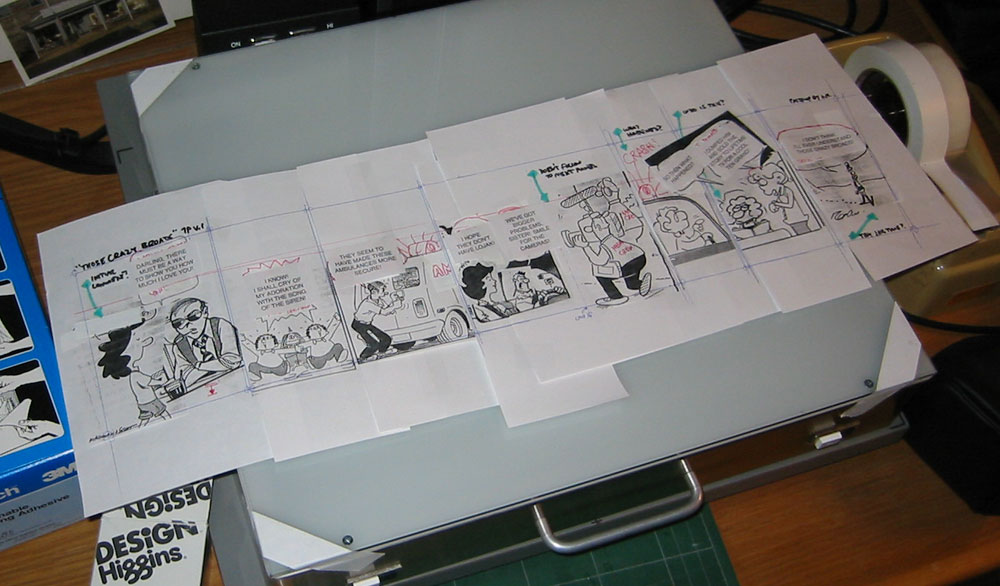

The compositing team will take the approved scripts and create rough evaluation versions, or “paste-ups”, of each. At this stage, there may be as many as six or as few as eight scripts approved.

Using stock imagery, similar panels from other comic strips, or existing footage of known characters, the compositors will assemble the paste-ups with tape and Glu-Stic so that the creative team can have a rough vision of what the final product will look like.

Only one strip will go to press, but as many as four may be focus-grouped in the final stage of selection. The process of focus-group studies, in which quantity values are assigned to every possible facet of every reaction expressed by a generally unopinionated group of otherwise-engaged mall patrons, helps the creative team cull the inferior concepts. Focus-group testing produces a matrix of numerical scores, determining empirically which homogenized product seems to be marginally better than the others.

IV. REVISIONS

Once the spec scripts have been turned into paste-ups, the process enters the long and soul-sucking process known as “executive revisions”. Every image is scrutinized; every line of dialogue is tweaked and double-tweaked; every element is examined until all involved have lost every shred of objectivity.

When this occurs, the “marking” process begins: each link in the chain of command, from Executive V. P. to Line Cook, will make a small, insignificant and possibly detrimental change to the product, thereby “marking their territory”, much like a dog does. Since this process by definition requires the input of each person, everyone’s job is secured.

When the strips are satisfactory to all involved, they go “to test.” This is the aforementioned process by which otherwise-unemployed individuals will stand in a shopping mall in an otherwise-ignored region of the country and accost passers-by, soliciting their everyman opinion. Experience has proven that this practice is the only possible way to determine the reaction of humans to the product, and therefore its quality or lack thereof.

V. THE DECISION

Finally, the Moment arrives. A specially-certified auditing agency compiles the testing results and delivers the scores to the Executive V. P., who makes the Decision of which strip to produce. Creating a kinda-weekly comic strip is a time-consuming and expensive process, so once the Decision is made and the actual strip finishing has begun, there’s No Going Back. For a strip with such a high standard of quality, the finishing process is very intensive. Its success is dependent largely on instinct borne from years of experience judging the temerity of the public consciousness.

The Decision arrives at the finishing campus in a sealed envelope. The above-the-line team, by virtue of this envelope, have symbolically passed the baton to the below-the-line craftsmen, having done everything possible to pave the way to artistic magnificence (and its close, burly cousin, commercial success).

The creation of the approved strip begins. Click here for Part II (of III)