This is a re-post, with photos newly added, of an essay I wrote a few years ago. It was originally published in the AOPA ePilot newsletter, March 2007.

My earliest memories are of pointing to the sky, having detected the far-off drone of a piston engine. Dad had been a pilot since before I was born. He flew a pea-green Cessna 172 from Rialto Municipal in Southern California. I can remember with crystal clarity those lazy Saturday afternoons at the airport, helping him push back the big hangar doors and leaning my small weight against the airplane’s struts as he pulled it into the sun.

I read him checklists, learning words like “aileron,” “magnetos,” and “pitot” that no one else in my first-grade class knew. I drew airplanes and helicopters all over every piece of paper I could find, proudly telling Dad that I was going to grow up to be a “helicopter designer.” I went to the library, looked up the addresses of every aircraft manufacturer I could think of, and sent them packets of drawings. (Grumman was the only one that responded, with a very nice letter and some glossy 8-by-10-inch photos of fighters.)

But, as a teenager, I had “better” things to do than hang out at the airport. I turned down invitations to fly out for breakfast — that would require getting up too early on weekend mornings. Eventually, I graduated from high school and moved away for college, beginning to build my life in a new city. I saw Dad less and less frequently. He talked occasionally about flying out to visit me, but then he lost his medical and sold the plane. At 75 years of age, he was grounded.

Over the next few years his health deteriorated further. He lost weight, and his energy flagged. When I did see him, he often sat slumped in his chair in a defeated pose I’d never encountered before.

And then, one morning, I got the call that the ambulance had come in the middle of the night to take him away. I rushed to the hospital and met, for the first time, a thin, sad figure that I hardly recognized as my father — so different from the strong, robust figure of my childhood. I drove him home that day, driving as carefully as I could, and knew that he was weak when he never once bothered to comment on my driving!

That night I told my then-girlfriend (now my wife) about how much I regretted passing up the opportunity to fly more with Dad when I’d had the chance. I mentioned that in the back of my mind, I’d always thought that I’d become a pilot someday. I’d just never done anything about it.

A few weeks later, for Valentine’s Day, she surprised me with a $49 introductory flight at a local flight school. I grinned like a chimp as I climbed into the school’s Piper Cherokee. When the Lycoming engine barked to life, it was as if a spark had jumped a gap in my heart — the love, vigor, and excitement of my childhood came rushing back.

As the instructor led me through some simple maneuvers, I realized that flying had to be part of my life again. The instructor complimented me on how comfortable I seemed in the sky and how sure my movements were — I told him that I’d done this before.

Before I left the airport that day, I bought a logbook and had the instructor sign the first line. I was working an evening shift at the time, so I worked flying lessons into my morning schedule. Within three months, I had my private pilot certificate and was as happy as I’d ever been.

But by now, Dad’s condition had gotten worse. His energy was very low. I’d told Mom about the flying lessons, but I didn’t tell Dad — I wanted it to be a surprise.

Dad still liked to go to the airport now and then to watch the airplanes and perhaps chat with some of the pilots. Mom told me about a fly-in breakfast that was coming up and said she would make sure he’d be there. When the day came, I took to the air, flying the one-hour cross-country to my hometown. As I taxied from the runway to transient parking, I found Mom leading Dad across the ramp toward me.

The first words out of his mouth were, “Why didn’t you tell me?” I laughed and gave him a hug.

The next thing he said was a string of admonishments — “Always watch the weather. Don’t spend too much money. Always be careful taxiing. Take the time to do a proper preflight.” Once I heard his strict tone, I knew that the old Dad was back, if only for the day.

Mom coaxed him into the cockpit, and I gingerly steered the plane onto the same runway that was featured so heavily in my favorite childhood memories. With a roar the Cherokee pulled us into the air, and a trip around the pattern rushed by all too quickly. On final, I asked him if he wanted to go around again. Feeling the stress of the flight, he declined. I let the plane down gently, pulled off the runway, and taxied back to parking.

Mom and I helped him climb down the Cherokee’s wing, and Mom asked him about the flight. “Sure, David’s a good pilot,” he said. Coming from him, this was high praise.

In the months that followed, he weakened further. I took any opportunity I could to visit him, even as his speech and breathing became labored. We discussed where I’d flown recently, and he told me stories of notable trips he’d taken. He continued to warn me about the hazards of not watching the weather, a lesson I’ve taken to heart.

Dad passed away about four months after the fly-in. My first flight ever had been as his passenger, and his last flight had been as mine. I continued to revisit the little Southern California airports that we’d been to together.

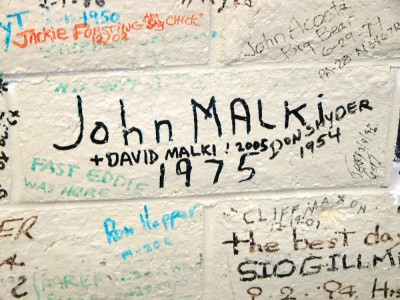

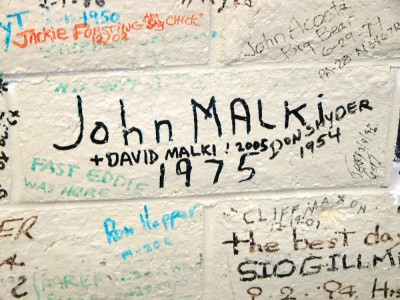

At Apple Valley, an airport in the desert northeast of Los Angeles, a restaurant wall is decorated with handwritten messages from 60 years’ worth of pilots who’ve passed through. Names and dates fight for space on the long, painted brick expanse. I remembered this place. I wondered if I’d written anything there.

I spent 15 minutes searching the wall, trying to find my own name. Instead, I found Dad’s — dated five years before I was born.

The ink had faded over the decades, and the name was partially covered by newer additions. I borrowed a marker from the waitress and inked over his signature, smiling as I recognized his familiar scrawl. I colored in his name and date, and then added my own beneath it. Mine was a little bit smaller, a little bit newer, a little bit sloppier — but it was right next to Dad’s.