In our recent discussion regarding the menace of the telephone (and electricity, and progress in general), I mentioned that there surely existed an exhortation against even the printing press, just as there seem to be curmudgeonly railings against every form of progress, in every generation. And the commenters came through!

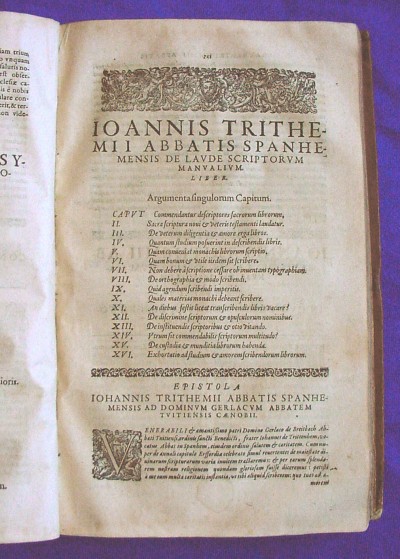

“Yoyo” mentions the fifteenth-century abbot Johannes Trithemius, author of the work De laude scriptorum manualium — “In Praise of Scribes.” (And yes, he grudgingly had to consent to get the tract printed in order to get people to read it.) Trithemius, a lexicographer who was also deeply interested in cryptography and steganography (the art of hiding messages), understood the benefits the printing press could bring to the scholar and the layman alike, but didn’t want it to replace the work that monks and scribes were doing, or become an excuse for monks to become lazy and neglect the devotional aspect of their work.

In that day, books (codices) were artifacts. They were large, and tremendously expensive and laborious to create, and made to be durable and to last forever. Fifteenth-century monastic scribes were the latest in a long line of clergy and learned-types sharing a bibliophile tradition stretching back to the Greeks, Persians and Romans of the pre-Christian era. And when books are rare and expensive, a library becomes no different from a cathedral slathered in gold and bedecked with stained glass: the bigger and more elaborate the collection, the more impressive. And a good library was a physical testament to the character of the collector. Trithemius was definitely on the side of books in general.

But in his tract, he homes in on the hand-writing of manuscripts in specific and meaningful ways. For example, much like a painter must begin his training by copying the masters, it is only by the act of copying the Scriptures can a scribe become truly in touch with the Word of God:

[The writer,] while he is writing on good subjects, is by the very act of writing introduced in a certain measure into the knowledge of the mysteries and greatly illuminated in his innermost soul; for those things which we write we more firmly impress upon the mind…While he is ruminating on the Scriptures he is frequently inflamed by them.

Plus, it was okay that the act of copying was hard. It built character, in Trithemius’ opinion, the same way as chopping wood (though to this “interior exercise,” i.e. exercise of the spirit, he assigned far more importance). For monks, labor was part and parcel of devotion, and if you weren’t good at writing, you could do binding, or painting, or for heaven’s sake practice. And it goes even further: the labor of manuscript writing was something for monks to do — for there was no greater danger for the devout soul than idleness.

For among all the manual exercises, none is so seemly to monks as devotion to the writing of sacred texts.

And this is really the crux of Trithemius’ argument.

He does spend some time talking about practical reasons that printed books weren’t anything to get bothered about: their paper wasn’t as permanent as the parchment the monks used (he even advocates the hand-copying of “useful” printed works for their preservation); there weren’t very many books in print, and they were hard to find; they were constrained by the limitations of type, and were therefore ugly. All perfectly functional reasons considering the circumstances of the time.

But the real kicker for him is what it means to hand-write a book even in the age of printing.

In a way, there’s a nobility to this. I can appreciate the tactile, artifact qualities of a book, or work of art that is hand-wrought even though machinery exists to create it. The idea that we as a culture place a giant premium on an item’s difficulty of creation has always been fascinating to me.

Think about it in terms of plagiarism: If I write an article that’s perfectly interesting, but you later learn that I plagiarized it, you don’t value the article anymore. You care less about the content of the article than you care about how I didn’t do the work.

People make the exact same argument about modern art: “My kid could do that!” If something doesn’t seem difficult, it doesn’t have worth.

Trithemius applies this as a gauge of devotion:

He who ceases from zeal for writing because of printing is no true lover of the Scriptures.

In other words, the way it has always been done is better, and the harder you have to work to keep doing it the old way, the more it proves you really care.

And I say that sentiment makes him a curmudgeon. Do you agree?

Quotes taken from The Abbot Trithemius (1462-1516): The Renaissance of Monastic Humanism by Noël L. Brann

Next week: Socrates vs. the written word itself!