Ray Bradbury passed away the other week. He was one of the first writers I had a cognizant appreciation of as a writer, as someone who deliberately made choices as to which words should go in which order to achieve a desired effect. My first art mentor, John Arthur, introduced me and my fellow students to Ray at an impressionable age, and we idolized him. I devoured Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles and The Illustrated Man, although as time went on I choked a bit on some of his other short stories — the language was so thick. I blame myself, however, not Ray.

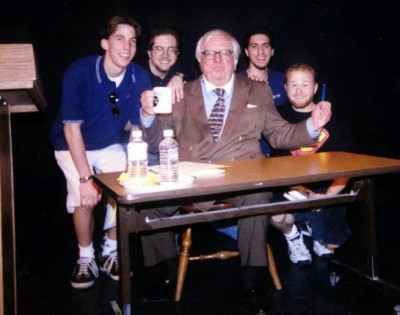

John took us to see Ray speak at a signing — it must have been about 1999 or so. I brought a friend’s copy of Fahrenheit 451 and my mom’s battered The Illustrated Man. When it was my turn to have my books signed, all I could stammer out was “You…uh…write very good.”

And that’s the picture up above: he smacked my face with his hand and said “Thank God!”

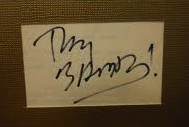

He signed both my books with an exclamation mark: “Ray Bradbury!” This was, shall we say, an instructive moment for me. I haven’t seen evidence that he signs his name like that often — I wish I could scan those books and show you how he did that day, but the Illustrated Man is somewhere in my mom’s house and the friend whose 451 I’d held onto for months suddenly became very interested in getting it back once I’d had it signed. Here’s a similar example I found online:

Anyway, the weird energy imparted by that exclamation mark in the signature stayed with me.

It’s after midnight as I write this. I’ve always felt comfortable at night; my own writing seems to come more easily at night. I remembered an old journal entry, just now, and looked it up and found the following:

Ray’s words crackle like ball lightning, never settling, dancing alight each concept, daring you to comprehend before they press on into the night. I’m listening to Something Wicked This Way Comes on CD, in my car, and when I concentrate and listen it’s like standing in a waterfall, weight pouring on me, trying to drink, feeling heavy and elated together.

Oddly, it’s very easy to get distracted from this book, sitting in traffic, realizing suddenly that I’ve been thinking about the chemical composition of jet contrails and a paragraph’s gone by and I’ve missed it. The words are oil-slick, loose and wriggling, and they have to be clutched and examined and tasted, or they slide off and flip away.

When I listen, they crush me, steamrolling with imagery. When I glance away, they pass by; but I glance quickly after and think back and still see the faint afterimage behind my lids. I hear the ringing echo and feel the warmth left in the air from their presence, like Montag in Fahrenheit 451. Even when I don’t hear them, they pass through me, speaking directly to my dreams. I drive, late on an empty freeway:

“Three in the morning,” thought Charles Halloway, seated on the edge of his bed, “why did the train come at that hour?”

For, he thought, it’s a special hour; women never awake, then, do they? They sleep the sleep of babes and children. But men, in middle age: they know that hour well. Oh, God!

Midnight’s not bad; you wake, and go back to sleep. One or two’s not bad; you toss, but sleep again. Five or six in the morning; there’s hope, for dawn’s just under the horizon.

But three, now, Christ. Three A.M.

Doctors say the body’s at low tide then. The soul is out, the blood moves slow; you’re the closest to dead you’ll ever be, save dying. Sleep is a patch of death. But three in the morn, full, wide-eyed staring, is living death. You dream with your eyes open. God, if you had strength to rise up, you’d slaughter your half-dreams with buckshot; but no, you lie, pinned to a deep well-bottom that’s bone dry.

You write very good, Ray. Thanks for everything.