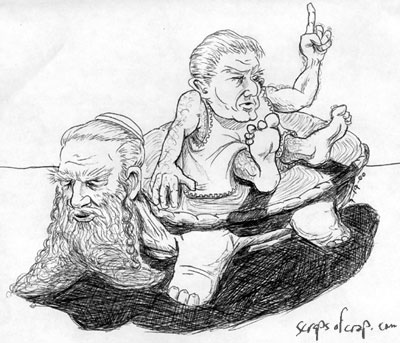

I should hasten to add that this drawing of Rabbi & Socrates that I found in an old sketchbook is a “latter-day” edition — it dates from 2000, a good three or four years after the original Rabbi & Socrates adventures. I remember drawing this as a sort of “fond look back.” I hope I can find some of the originals.

This particular piece, I believe, was drawn to accompany a Rabbi & Socrates children’s book manuscript (which never got very far along). However, I’m better at keeping track of old writing than old drawings. Here’s Chapter 1 from The Extraordinary Journeys of Rabbi & Socrates, written in 2000.

***

1 : Gregory

“I hate it when they fight.”

Gregory Elliott flopped onto his bed, the covers still undone from this morning, and buried an eleven-year-old head deep into a pillow. It was rather stifling, and smelled just faintly of shampoo and sweat, but it covered his ears and muffled the shouting that faded into his room from down the hall. He twisted about and dug his fists a little into the pillowcase, but the sounds were still there.

“I’ll just have to talk to myself to drown them out,” he said for no reason other than to say it. “It’s the only thing that works, really.”

The pillow soaked up his voice and, to some extent, his fear. This was the same pillow that’d always listened to him, even when he had nothing important to say. His parents had walked in on him, a few times, while he was talking to his pillow, and his father had looked at his mother and they had quietly shut the door and left him be. They couldn’t seem to do anything quietly right now, though.

Gregory took as deep a breath as the pillow would allow and started to talk. “I wish Mom and Dad wouldn’t yell at each other. I wish that Dad wouldn’t get mad at Mom for such little things. I wish Mom wouldn’t cry so much.”

He didn’t cry, anymore. He saw how useless it was for Mom to cry, and figured that nothing was really solved by crying. Instead, when he got sad, like he was now, he’d imagine that he was someplace else. The pillow that smothered his senses became a marshmallow, huge and warm and sugary, and he was falling into the sticky softness of it just as it was falling through the sky from some giant cup of hot cocoa. He began to imagine how it would smell, sweet, with a hint of the chocolate from the hot cocoa seeped into it — and as he imagined it, he almost thought that he could smell it. Almost.

“I must be getting pretty good at make-believe,” Gregory told the pillow, and smiled a soft, eleven-year-old smile. “I could almost smell the cocoa, even. Whoever made it put cinnamon in it, like Gramma.”

He imagined that the marshmallow was falling through the air, and that he was sinking slowly into it while it twisted and tossed. His stomach took a little leap. He smiled again, and squeezed his eyes shut tighter. The stickiness pulled at his eyebrows.

“That’s kinda weird,” he thought. He couldn’t hear his parents at all, now.

The marshmallow hit the ground.

“That’s even weirder,” Gregory said. He felt the softness of the impact as he sunk deeper and deeper. The sweet smell was overpowering.

Gregory furrowed his brow and let go of the pillow. He tried to sit up — but the marshmallow was caving in on him, trapping him. He flailed his arms, but they were held uselessly by unseen mushiness. He tried to pull his head away from his pillow, but couldn’t. The sugary smell threatened to stifle him.

“Help!” he cried, barely moving his jaw. “Help! Mom! Dad! Help!”

“Now, listen, son,” came a soft voice from somewhere above him. It belonged to nobody he knew.

“Would it be fair to say that you’re in a rather sticky situation, there?”

“Yes, of course,” he choked. “Please, help!”

“Would it be fair to also say that you can’t free yourself without my assistance? Or that of someone similarly inclined?”

Gregory didn’t quite understand, but was in no position to debate. “Yes, please! I can’t breathe!”

“Then, logically, you would like my help.”

Gregory was very confused, but saw that it would be best to agree. “Yes, I would!”

“So, then, my moral responsibility as an autonomous individual acting conscionably would be to assist you in your predicament. Would you agree?”

Gregory stopped short of responding. Half of those words were foreign to him. He was just opening his mouth when another voice met the first. It was a bit deeper, and accompanied by scrabbling at the marshmallow stuff above him.

“Feh! The boy’s in trouble, Socrates, and you’re playing twenty questions with him. Maybe for once it would be better to open your eyes instead of your mouth.”

Gregory struggled towards this new voice. Whoever it was, Gregory wanted his assistance. The first voice spoke again.

“Rabbi, would you agree that on most occasions we share the opinion of –”

“Quiet with the questions! I can almost reach his hand. I think you can reach it.”

Gregory felt a strong hand grip his wrist and begin to pull him free of the marshmallow. He closed his eyes as the stickiness slid around him, his other hand still clutching his pillow. A few seconds later, and cool air rushed into his lungs. He stumbled across what seemed like acres of marshmallow and collapsed onto the ground, his hands finding packed dirt. He coughed a few times and scrubbed at his eyes and finally managed to get them open.

“You see, he’s all right.” The second voice spoke. Gregory made out a vague, dark mass approaching him. “It’s all right, kaddishel. We’ll get you some water. You can cleanse yourself. Keep your eyes closed if it’s more comfortable.”

Gregory nodded and rubbed his face. He was covered all over with clinging bits of marshmallow. The voice addressed him again.

“Just breathe deeply. We’ll take you to the water.” Gregory felt something smooth and cold slide past his leg.

He shivered. “Socrates! Lead the boy to the water.”

“I think you would agree, Rabbi, that he would like to wash up.”

“And that is what he shall do.”

The firm hand took Gregory’s, again, and led him across the packed-earth plain to a slightly more sandy region.

He slowly stepped into the water.

“Would it be true to say that you’d prefer to wash your clothes out separately?”

Gregory paused for a moment, up to his ankles in slow but cold current, and nodded. He peeled his shirt from over his head and splashed water into his face. He walked into the water until he was waist deep and then removed his pajama pants, which were taken from him by the unseen Socrates. With a deep breath, he plunged his head into the water.

It was very cool water, and felt very fresh on his face. Cheeks bulging with air, Gregory scrubbed at his face and hair and hands, going back up for air and down again several times. Gasping, he emerged, and turned to face his rescuers.

“A refreshing wash, I hope,” said Rabbi, and Gregory wiped the water from his eyes to focus. What looked like a giant tortoise sat on the shore, with a small man perched on the shell. Rabbi’s voice spoke again, and Gregory realized that the tortoise had the head of a thick-bearded man.

“Are you all right?” Rabbi said. The man on the tortoise’s back crossed his arms.

Gregory squinted and took a step closer.

“It would appear that he’s a bit confused,” Socrates, perched on the shell, said. He ducked his head to address Rabbi. “Would you agree that we should probably learn where he came from?”

Rabbi nodded. “He fell from the sky like a dead cloud. Feh!”

Gregory stared at the odd pairing, unsure exactly what to say or how to react. He opened his mouth to attempt insight, and as the two turned to face him they opened their mouths as well. Their eyes went wide, their voices fell silent, and a huge shadow swept across Gregory’s body. He shivered.

Hot breath coursed down Gregory’s back. “Don’t turn around, man-pup,” it seemed to say. Gregory began to quake, searching Rabbi and Socrates for any clue as to the proper reaction, but the peculiar pair was merely staring behind him, unmoving. Socrates’ bottom lip began to quiver.

The voice spoke hot ire into Gregory’s ear. “Don’t trust these two any farther than you’d trust a fly buzzing around your face.”

Gregory scowled. A fly was certainly bad enough, but smelly breath burning the back of his neck was certainly worse. He wrinkled his nose.

A jet of noxious steam cascaded around his head. “I can read your thoughts, man-pup. You can’t hide from me.”

Gregory pondered this a moment. The breath swirled around his face.

“How do I get home?” he asked.

The breath stopped. Rabbi and Socrates closed their mouths but widened their eyes. Gregory firmed his resolve.

“You know what I’m thinking, right?” he challenged. “So you must know how I got here. How do I get home.”

“You don’t want to go home. That’s why you came here, insolent man-pup.” The voice was a touch more hesitant. Gregory pushed his advantage.

“I don’t know what insolent means, but if it means I want to go home, then yes, I’m insolent,” he said. He turned to look at his accuser. A blast of steaming stench stopped him. He coughed, once, twice.

“Don’t turn around!” the voice hissed. “I mean it. You won’t live to regret it.”

It was the voice of Socrates that filled in Gregory’s speechlessness. “Would you agree,” the small man pondered to apparently nobody in particular, “that this situation borders on the unusual?”

“Of course,” Rabbi replied. Gregory waved at the thickening cloud of unpleasant gas.

“Do you follow my conjecture, then, that something here is not quite what it seems?”

“A very reasonable conjecture,” Rabbi said.

Gregory turned and faced his assailant. He blinked a few times, not seeing anything but the billowing cloud of steam, and then looked at his feet. There squatted a little chimpanzee, withered and wrinkled, holding a canister that looked like a fire extinguisher. The chimp’s eyes were wide, and it held the canister in front of its face. A gnarled hand squeezed the lever. “I’m warning you,” came the voice.

Gregory scowled. The chimp chittered, then dropped the canister and glanced about furtively. Tiny, leathery wings exploded from its back. Gregory flinched. The chimp took several uneven steps backwards and flew rapidly away.

“I…I’ve never seen anything like that,” Gregory said when at last he regained the faculty of speech.

Rabbi meandered his slow tortoise body to the canister and spat, weakly. “Feh! I’ll be just as happy if I never see one again. They’re pests is what they are. Eat ashes and kuck out charcoal. A shandeh un a charpeh.” He rubbed a hard toenail in a pile of soot that took the shape of primate footprints.

“It seems to follow that he made some bargain with a rhode,” added Socrates, looking over the canister, “or that he is a cunning scavenger.”

Gregory looked back and forth between the small, bearded man and the man-headed tortoise. “I just don’t know how to react to this,” he said, and sank to a sitting position.

Rabbi furrowed his massive brow. “Of course not. You’re just a kaddishel. Young, you know.” He nudged Socrates with a foot. “Turn that thing around, are there any marks on it?”

Socrates examined the canister. “It would seem to me that the rhode who lost this did so willingly. Would you agree that there are no marks of a struggle, and none of the deterioration that would accompany the host’s death?”

“Yes, yes.” Rabbi curled his lips. “If you would hold it so I could see it –”

Gregory looked over at the canister, smooth and metallic, red with a hint of brown. The color of drying blood. “What is that thing?”

Rabbi turned to face him, long, curling earlocks swaying with the motion. “It’s the voicecan of a rhode. They can’t naturally talk, so they make these for themselves. It’s some sort of ritual in their culture. They don’t like to part with them, either.”

Gregory opened his mouth to ask what a rhode was, then shook his head. “How did the monkey get hold of it?”

“What monkey?” Rabbi looked at Gregory blankly. “Oh, the little scavenger. I don’t know what he was. But some rhodes will bargain their voicecans off for other things, and the scavenger must have been using the can to intimidate its prey.”

Gregory looked at the dry, empty horizon where the scavenger had disappeared. “It said it could read my mind.”

“Feh.” Rabbi scowled. “Those guys are cunning, sure. But telepathic? Er bolbet narishkeiten. No way.” He turned back to Socrates. “Let me get a better look at that.”

Gregory looked at the barren, flat landscape and shivered. A breeze ruffled his hair, hot and foreign. This place was altogether unknown to him. Much as he had wished otherwise, now he thought that nothing would be better than simply to be home again.

He approached where the pair was mumbling to one another. “Excuse me.”

Socrates looked up. “Would you agree that the scavenger having a rhode voicecan indicates that something is amiss in this vicinity?”

Gregory shook his head. “I just learned that I don’t know anything about this place. I don’t know what’s right or wrong. For all I know, you guys could be perfectly normal.”

Socrates exchanged a glance with Rabbi, then looked back up at Gregory. He seemed at a loss for words, so Rabbi filled in. “We are. We didn’t want to mention it, since we figured you were probably sensitive about your handicap –”

Gregory scowled. “What handicap?”

Rabbi spoke slowly, choosing his words. “You are a bit strange in that you are much larger than any other child I have ever seen. Not that it is a bad thing, or that –”

Gregory’s mouth fell open. “You are a turtle with a man’s head!” he finally cried. “How much more strange can you get?”

Rabbi looked over at Socrates. “I am the proper age,” he said, puffing himself up as much as he could inside a shell. “I started the transition at the proper age, and it is progressing properly. I see nothing strange about it.”

Socrates nodded. “I think you would agree, he is a fine specimen for his age.”

Gregory turned around in circles a few times, his hands going up and down, searching for the right words. This was unlike anything he had ever seen before. His desire to return home grew stronger by the minute.

“Somehow,” Gregory said, “I was brought here. I’m not from this place –”

“That’s for sure,” Rabbi said, and he and Socrates chuckled.

“No, no, don’t laugh!” Gregory cried. “I need to know how to get –”

“Hey!” Rabbi cried, his attention suddenly diverted to somewhere behind Gregory. “It’s K. He’s probably wondering what took us so long.”

Socrates nodded. “It would seem like a probable conjecture.”

Gregory sighed and turned around. Approaching them was a huge armadillo, waddling from side so side. Gregory noted that the armadillo’s head was that of an older Asian man. His hair was pulled up in a topknot.

“Hey, there, K!” Rabbi shuffled his turtle body around to address the new arrival. “We were just on our way, when we noticed this little boy in a marshmallow.”

K nodded. “The boy-in-the-marshmarrow excuse. I never know when to believe you. Last time the evidence wasn’t here to back it up, eh?” He turned to Gregory. “My name is K. You are welcome to come, too, to tea.”

Gregory nodded. “Thank you, but I really have to see about getting home. I don’t know where to begin, but the sooner I start the sooner it’ll happen, I guess.”

K laughed, a sound like boulders crunching together. “Tea helps you to think. Come arong. You come for tea.”

Socrates began walking briskly in the direction K had come, still clutching the voicecan. “It is inarguable that relaxation and nourishment bolster important decision-making capacities, is it not?”

K turned and followed. “No, no, Socrates. No more of your argument tonight. This is just time for tea, not for phirosophy of existence.” He turned his head back towards Gregory, still standing stunned. “Come now. And perhaps I can help you how to get home.”

Gregory blinked a few times, then followed.