In my last post on the ethics of photo retouching, and how it’s been prevalent since the birth of photography, commenter Pelotard mentioned the official Soviet portraits of Gorbachev:

…And how they always conveniently seemed to leave something out.

This got me thinking about idealized portraiture in general. It goes back as long as portraiture itself, of course; early classical portraits of emperors and such tended to cycle through emphasis on either a rugged, realistic appearance (as would befit a warrior and statesman) or an angelic, unblemished appearance (as would befit a god). In the same way, later emperors (such as Constantine) saw value in associating themselves in the public eye with prior, well-regarded emperors. Constantine went so far as to wear the same haircut as Trajan:

(In my interview with the world’s foremost beard expert, Dr. Christopher Oldstone-Moore discusses a similar trend in the history of beards. Alexander the Great wished to be seen as a god, i.e. youthful and athletic, so he wore no beard. Hadrian, however, wished to be seen as a philosopher and thinker, so he did wear a beard. It was a cyclical fashion.)

There are cycles in contemporary fashion too, of course: the recent few years have seen a huge rise in oversharpened, deliberately un-airbrushed celebrity portraits like those of Martin Schoeller. But as you might imagine, I’m personally particularly interested in how people felt on the subject 100+ years ago.

The arts have often, throughout history, been tied up with religion; the act of creation has often been seen as a tribute to divinity, an imitation of God and, by virtue of art’s power to stir the emotions of the viewer, a righteous calling to aid in devotion. I found reference to idealism’s employ as a deliberate, spiritual tool in Christopher Wordsworth’s 1879 book Miscellanies, Literary and Religious, Vol. 2. Wordsworth first quotes famous painter (and noted idealist) Sir Joshua Reynolds:

“A mere copier of Nature can never produce anything that is great, he can never raise and enlarge the conceptions or warm the heart of the spectator; a genuine painter must strive for fame not by neatness of imitation, but by captivating the imagination. All the arts receive their perfection from an ideal beauty, superior to what is found in individual nature.”

Wordsworth then goes on to discuss artistic depictions of the Christian cross — that is, the cross shape itself as an icon — vs. the crucifix, the more traditionally Catholic representation which also includes the bodily figure of Christ. “In the noble simplicity, and sublime abstraction, of the Cross,” says Wordsworth, “the Imagination is left free to crown sorrow and suffering with a diadem and halo of glory. But in the Crucifix, the Imagination is confined by the senses, and is riveted to the contemplation of pain and shame and death, which were only transitory.”

In other words, concentrating the viewer’s attention on the earthly — the “realistic” — aspects of the Crucifixion should not be the point of the art. The point of the art should be to avoid the earthly aspects; to prompt, instead, contemplation of the divine.

He goes on to address landscape and portrait painting specifically:

What is it that imparts a charm to the mellow tints of sunset in the pictures of Claude or Turner, and to the rich foliage of the trees, and to the quiet bridge over the flowing river, and to the cattle reflected in the water, and to the old ivy-mantled tower or ruined temple, and to the calm expanse of the broad lake, and to the delicate hues of aerial distance melting away into infinity? Is it not the feeling that under the influence of objects like these we are transported from the petty cares and brief sorrows of to-day to a far-off age, and to a distant land of an ideal Arcadia, a poetical Elysium, a spiritual Paradise? […]

So it is also with Portrait-painting. At the present day by the general use of Photography (very valuable in representing buildings and in reproducing manuscripts), Portrait-painting is in danger of being degraded to the low level and servile drudgery of endeavouring to execute facsimiles. It does not portray the mind [i.e. the spirit] by means of the mind, but (may we not rather say?) it copies a machine [the human body] by the help of a machine. It therefore fails of producing a real likeness.

For a man is not what he seems to the eye to be at a particular moment of his existence, seized upon by the spasmodic shock of a mechanical process, but what he is in his generalized essence as discerned by the intuitive genius of the Artist. The genuine Portrait-painter will indeed be careful to preserve the personal identity of the subject, but he penetrates below the surface into the inner recesses of the mind. And although his art is affected by conditions of time and space, it goes beyond the limits of both, and reveals some gleams of eternity.

In Wordsworth’s view, a human being is simply a machine made of meat: its spark of divine is contained within, and no slavish artistic representation of wrinkles and freckles could ever reproduce that which is truly unique and valuable about a person.

This is a very interesting perspective to port over to the question of modern-day celebrity photography: for is it not true that the essence of a celebrity is their image, the idea of who they are? The person with wrinkles and dry elbows and saggy jowls who looks in Angelina Jolie’s mirror each morning bears little connection to the simulacrum, the manufactured construct of “Angelina Jolie” that millions of people recognize and experience in a shared way via popular media. In the same way that Wordsworth advised contemplation of the cross over the crucifix so as to focus attention on the noble idea of Christ, where lies the true value, rather than all the nitty-gritty details which may not really be of consequence — in a world where the shared conception of a celebrity is what drives box-office grosses and sells magazines, is it any surprise that that conception should be crafted into an object of adulation, a higher-than-human ideal?

Ah, but what are the consequences of this sort of thing? When normal folks like you and I look at the magazine covers, the argument goes, we can’t identify with those strange, perfect beings. We, as a class of imperfect people, feel alienated from them; we can’t ever believe we could be like them. This destroys our self-esteem.

So how much worse might this alienation be if you are a devoted Christian, and the object that seems so foreign and alien to you is Christ?

One clue is found in an essay entitled “The Portrait Art” from the 1884 book Euphorion Vol. 2, a collection of essays by Vernon Lee, mainly on art in antiquity and the Renaissance. Lee writes:

Real and ideal—these are the handy terms, admiring or disapproving, which criticism claps with random facility on to every imaginable school. This artist or group of artists goes in for the real—the upright, noble, trumpery, filthy real; that other artist or group of artists seeks after the ideal—the ideal which may mean sublimity or platitude. We summon every living artist to state whether he is a realist or an idealist; we classify all dead artists as realists or idealists; we treat the matter as if it were one of almost moral importance.

Now the fact of the case is that the question of realism and idealism, which we calmly assume as already settled or easy to settle by our own sense of right and wrong, is one of the tangled questions of art-philosophy; and one, moreover, which no amount of theory, but only historic fact, can ever set right. […]

The pupil of Perugino will, indeed, wait patiently to begin his work until he can find a model fit for a god or goddess; while the fellow-craftsman of Rembrandt will be satisfied with the first dirty old Jew or besotten barmaid that comes to hand.

But the realistic Dutchman is not, therefore, any the less smitten with beauty, any the less eager to be ornamental, than the idealistic Italian: his man and woman he takes indeed with off-hand indifference, but he places them in that of which the Italian shall perhaps never have dreamed, in that on which he has expended all his science, his skill, his fancy, in that which he gives as his addition to the beautiful things of art—in atmosphere, in light, which are to the everyday atmosphere and light what the patiently sought for, carefully perfected god or goddess model of Raphael is to the everyday Jew, to the everyday barmaid, of Rembrandt.

Lee’s examination (and the whole thing is well worth a read) of realism vs. idealism spends some time clarifying the difference between the two with respect to the aims and goals of the artist.

For example, some artists are craftsmen whose frescoes serve as much a decorative purpose as the arches and gables of the building they adorn — and for them, beauty and loveliness and perfection are noble goals.

Others, however, feel their art should be a record, either of the truth of the world as they see it or — in the case of devotional scenes of saints and so on — the truth of a world as they wish others to understand it. Realism is for them a tool to connect a viewer viscerally with a scene that they did not experience firsthand:

In Giotto’s frescoes at Santa Croce—one of the most lovely pieces of mere architectural decoration conceivable—there are around the dying and the dead St. Francis two groups of monks, which are astoundingly realistic. The solemn ending of the ideally beautiful life of sanctity which was so fresh in the memory of Giotto’s contemporaries, is nothing beyond a set of portraits of the most absolutely mediocre creatures, moral and intellectual, of creatures the most utterly incapable of religious enthusiasm that ever made religion a livelihood. They gather round the dying and the dead St. Francis, a noble figure, not at all ecstatic or seraphic, but pure, strong, worn out with wise and righteous labour, a man of thought and action, upon whose hands and feet the stigmata of supernatural rapture are a mere absurdity.

The monks are presumably his immediate disciples, those fervent and delicate poetic natures of whom we read in the “Fioretti di San Francesco.” To represent them Giotto has painted the likeness of the first half-dozen friars he may have met in the streets near Santa Croce: not caricatures, nor ideals, but portraits.

Giotto has attempted neither to exalt nor to degrade them into any sort of bodily or spiritual interestingness. They are not low nor bestial nor extremely stupid. They are in various degrees dull, sly, routinist, prosaic, pedantic ; their most noteworthy characteristic is that they are certainly the men who are not called by God. They are no scandal to the Church, but no honour; they are sloth, stupidity, sensualism, and cunning not yet risen to the dignity of a vice. They look upon the dying and the dead saint with indifference, want of understanding, at most a gape or a bright look of stupid miscomprehension at the stigmata: they do not even perceive that a saint is a different being from themselves…

And too much idealism in devotional art, Lee argues, leads to a disconnect from the message the art is trying to convey:

With these frescoes of Giotto I should wish to compare Fra Angelico’s great ceremonial crucifixion in the cloister chapel of San Marco of Florence…

Artistico-religious prudery has made Angelico, who was able to foreshorten powerfully the brawny crucified thieves, represent the Saviour dangling from the cross bleached, boneless, and shapeless, a thing that is not dead because it has never been alive. The holy persons around stand rigid, vacant, against their blue nowhere of background, with vague expanses of pink face looking neither one way nor the other; mere modernized copies of the strange, goggle-eyed, vapid beings on the old Italian mosaics.

This is not a representation of the actual reality of the crucifixion, like Tintoret’s superb picture at S. Rocco, or Dürer’s print, or so many others, which show the hill, the people, the hangman, the ladders and ropes and hammers and tweezers: it is a sort of mystic repetition of it…

A row of saints, founders of orders, kneel one behind the other, and by their side stand apostles and doctors of the Church; admitting them to the sight of the superhuman, with the gesture, the bland, indifferent vacuity of the Cameriere Segreto or Monsignore who introduces a troop of pilgrims to the Pope; they are privileged persons, they respect, they keep up decorum, they raise their eyes and compress their lips with ceremonious reverence; but, Lord! they have gone through it all so often, they are so familiar with it, they don’t look at it any longer; they gaze about listlessly, they would yawn if they were not too well bred for that.

The others, meanwhile, the sainted pilgrims, the men whose journey over the sharp stones and among the pricking brambles of life’s wilderness finds its final reward in this admission into the presence of the Holiest, kneel one by one, with various expressions: one with the stupid delight of a religious sightseer; his vanity is satisfied, he will next draw a rosary from his pocket and get it blessed by Christ Himself; he will recount it all to his friends at home. Another is dull and gaping, a clown who has walked barefoot from Valencia to Rome, and got imbecile by the way; yet another, prim and dapper; the rest indifferent looking restlessly about them, at each other, at their feet and hands, perhaps exchanging mute remarks about the length of time they are kept waiting; those at the end of the kneeling procession, St. Peter Martyr and St. Giovanni Gualberto especially, have the bored, listless, devout look of the priestlets in the train of a bishop.

All these figures, the standing ones who introduce and the kneeling ones who are being introduced, are the most perfect types of various states of dull, commonplace, mediocre routinist superstition; so many Camerlenghi on the one hand, so many Passionist or Propagandists on the other: the first aristocratic, bland and bored; the second, dull, listless, mumbling, chewing Latin Prayers which never meant much to their minds, and now mean nothing; both perfectly reverential and proper in behaviour, with no more possibility of individual fervour of belief than of individual levity of disbelief: the Church, as it exists in well-regulated decrepitude.

And thus does the last of the Giottesques, the painter of glorified Madonnas and dancing angels, the saint, represent the saints admitted to behold the supreme tragedy of the Redemption.

The ideal, as Lee describes Fra Angelico’s painting, is banal; the people seem uninterested, their expressions disconnected from anything approaching anything we should want to invest ourselves in as viewers. In contrast to this, Giotto’s painting mentioned earlier doesn’t trouble itself prettying up the faces, or wrapping halos around the heads of its saints; it’s instead, by virtue of its groundedness, a snapshot of something approaching a scene we might have glimpsed in our own life, people we may have passed on the street. Thus we will spare a second look at it — and thus may its message reach us.

The idea that hyper-realism can insert an observer into a scene seems an obvious one. It’s done every day in movies, video games, and even in fine art to provoke a visceral reaction: check out the work of sculptor Duane Hanson, or photographer Charlie White (NSFW), or basically all of surrealism.

So it’s what Lee is arguing for, in stark contrast to Wordsworth: in order to understand something like the Crucifixion, for example, you must find something relatable about it. You must find handholds to catch your understanding on; you must feel like you are there.

But where does this leave the ideal of beauty? I love the conclusion that Lee reaches, a notion that affords equal power in art to both beauty and realism:

[The] idealistic artist is left without any resources when bid to paint an ugly man or woman. With the realistic artist, to whom the man or woman is utterly indifferent, to whom the medium in which they are seen is everything, the case is just reversed: let him arrange his light, his atmospheric effect, and he will work into their pattern no matter what plain or repulsive wretch.

To Velasquez the flaccid yellowish fair flesh, with its grey downy shadows, the limp pale drab hair, which is grey in the light and scarcely perceptibly blond in the shade, all this unhealthy, bloodless, feebly living, effete mass of humanity called Philip IV. of Spain, shivering in moral anaemia like some dog thorough bred into nothingness, becomes merely the foundation for a splendid harmony of pale tints.

Again, the poor little baby princess, with scarce visible features, seemingly kneaded (but not sufficiently pinched and modelled) out of the wet ashes of an auto da fé…this childish personification of courtly dreariness, certainly born on an Ash Wednesday, becomes the principal strands for a marvellous tissue of silvery and ashy light, tinged yellowish in the hair, bluish in the eyes and downy cheeks, pale red in the lips and the rose in the hair; something to match which in beauty you must think of some rarely seen veined and jaspered rainy twilight, or opal-tinted hazy winter morning. Ugliness, nay, repulsiveness, vanish, subdued into beauty, even as noxious gases may be subdued into health-giving substances by some cunning chemist.

The beauty of this work is not in the subject, but in the work itself. The sublime divinity that artists never could touch by rendering Christ or the saints or anybody else as a wax mannequin, unblemished by any earthly vulgarity, is warmly embraced when creating, as Lee says, “a beautiful picture out of an ugly man.”

That’s all I have, but I just love Lee’s descriptions so much that I’m going to leave you with one more:

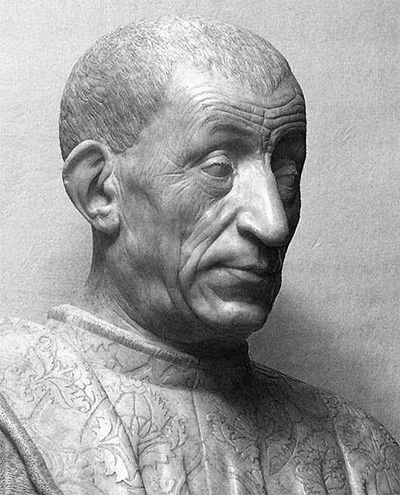

The very perfection of this kind of work is Benedetto da Maiano’s bust of Pietro Mellini in the Bargello at Florence. The elderly head is of strongly marked osseous structure, yet fleshed with abundant and flaccid flesh, hanging in folds or creases round the mouth and chin, yet not flobbery and floppy, but solid, though yielding, creased, wrinkled, crevassed rather as a sandy hillside is crevassed by the trickling waters; semisolid, promising slight resistance, waxy, yielding to the touch. But all the flesh has, as it were, gravitated to the lower part of the face, conglomerated, or rather draped itself, about the mouth, firmer for sunken teeth and shaving; and the skin has remained alone across the head, wrinkled, yet drawn in tight folds across the dome-shaped skull, as if, while the flesh disappeared, the bone also had enlarged. And on the temples the flesh has once been thick, the bone (seemingly) slight; and now the skin is being drawn, recently, and we feel more and more every day, into a radiation of minute creases, as if the bone and flesh were having a last struggle. Now in this head there is little beauty of line (the man has never been goodlooking), and there is not much character in the sense of strongly marked mental or moral personality. I do not know, nor care, what manner of man this may have been. The individuality is one, not of the mind, but of the flesh. What interests, attaches, is not the character or temperament, but the bone and skin, the creases and folds of flesh. And herein also lies the beauty of the work.

Imagine this paragraph read by Patrick Stewart. SOMEBODY PLEASE MAKE THIS HAPPEN

…commenter Pelotard mentioned the official Soviet portraits of Gorbachev……And how they always conveniently seemed to leave something out.

Based on the picture at the link, I assume you mean the double-chin? >grin<

Wonderful writing! I think of Wondermark as a “retouching” of history, so your last two articles have been very enlightening.

And yes, Patrick Stewart would make that last paragraph resonate with gravity. I watched his turn at Macbeth on Netflix the other night and for a treat today, will listen to his narration of Rick Wakeman’s “Return to the Centre of the Earth” (which you should give a listen if you haven’t heard it).

Since you (quoting Lee) mention King Philip IV, you might be interested to know that he was signing autographs recently in New York. ( http://improveverywhere.com/2011/03/06/king-philip-iv/)

More fun facts about Roman Emperor hair: what we now call the “Caesar” cut was first adopted by Augustus in an attempt to look more like his adoptive father Julius Caesar. But Julius was bald and had what is probably history’s first recorded combover (the biographer Suetonius said he “called his hair up from the back of his head”) while Augustus wasn’t — the short hair, combed forward a bit over the forehead, was his attempt to simulate a combover, and of course it turned out to be much emulated.

“So how much worse might this alienation be if you are a devoted Christian, and the object that seems so foreign and alien to you is Christ?”

From an orthodox (little “o”) perspective, Christians are right to feel humbled and imperfect in light of who they believe Christ is. The counterpoint to this is that they are to feel valued in that God saw fit to sacrifice the said Christ in order to redeem them. It’s a concept I often struggle with, as I tend to view humans as, on the whole, scumbags. I must constantly remind myself that John 3:16 says that God loves the world, and it is not my place to question why.

Good insight, David!

I feel that Lee misunderstands the purpose of painting such as Angelico’s. Angelico’s painting is an icon (though not as ikon-ic as those of the East) of the Crucifixion, and thus will go about the task of projecting its message in a way different than Giotto’s paintings.

Is it just me or does Pietro Mellini look a bit like Bill Cosby making his pudding face?

@Desert Plah – perhaps this is semantic, but I think that Christians are supposed to feel humbled by Christ in a moral or spiritual sense – not disconnected from him in a human sense, as the fact that he was a human being is of great significance. In my opinion, to find him unrelatable misses the point, as he spent most of his life relating to other people. That said, I don’t really see the cross vs. crucifix distinction as being particularly meaningful, but I see why someone would.

@David – this was a very compelling article. I’ll probably be thinking about it a while.

Trajan’s dates are wrong (as given under the photo of his portrait bust). He was emperor from A.D. 98 to 117.

DM: Thanks for the correction, it’s been changed!

Have you seen this link? The photos are eerily reminiscent of your comics… http://www.buzzfeed.com/mjs538/50-unexplainable-black-white-photos