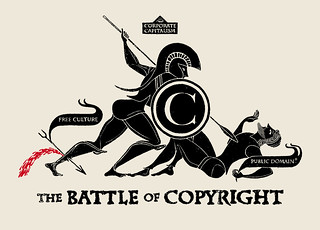

Source: Christopher Dombres via Flickr

The U.S. Copyright Office has launched a new Fair Use Index:

Fair use is a longstanding and vital aspect of American copyright law. The goal of the Index is to make the principles and application of fair use more accessible and understandable to the public by presenting a searchable database of court opinions, including by category and type of use (e.g., music, internet/digitization, parody).

The Fair Use Index is designed to be user-friendly. For each decision, we have provided a brief summary of the facts, the relevant question(s) presented, and the court’s determination as to whether the contested use was fair.

The Index itself is a series of summaries of key legal decisions regarding copyright and fair use, largely from the last sixty years.

It’s super interesting to me! Wondermark is, of course, created using images from the public domain. Which is not the same as fair use; public domain works have no copyright, whereas fair use is made of works that are copyrighted.

But copyright in all its gleaming facets is still a topic near and dear to my heart as an artist, author, and attentive internet citizen: I’ve written a fair amount about copyright and intellectual property.

The Fair Use Index includes some watershed copyright cases, such as 1978’s Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, the precedent that defines the infringement threshold for copying copyrighted characters for “parody” purposes.

It might be said that under the Air Pirates test, the entire product line of the t-shirt website TeeFury is illegal, and I notice that very conveniently, most of their designs are only available in strictly limited, before-they-can-send-us-a-cease-and-desist editions.

Also included is the “Betamax” case, 1984’s Sony Corporation v. Universal City Studios, which ruled that recording a free broadcast of live television onto videotape for later home viewing — referred to as “time-shifting” — was, indeed, legal. “Home taping” (of both television and radio) was the big I.P. boogieman threat before “piracy”, and this court decision was what enabled the VCR, as a consumer device, to exist at all.

In browsing, I also came across some interesting cases I hadn’t heard about before, such as:

• 1985’s MGM v. Honda Motor Corp., in which MGM sued — and won — claiming that a spy-themed Honda commercial was too reminiscent of their copyrighted character, James Bond (and that it damaged the James Bond brand to show him in a Honda);

• 2004’s MasterCard v. Nader 2000, in which MasterCard sued — and lost — a copyright infringement suit against Ralph Nader’s presidential campaign commercials which copied/parodied its “priceless” slogan;

• 2006’s CleanFlicks v. Soderbergh, in which the company CleanFlicks, which edited objectionable content out of Hollywood movies and re-sold them to customers who preferred them that way, sought a declaratory judgment that doing so was legal — and lost. They thought they’d be OK because they’d buy a copy of the actual DVD, add in the edited version, and re-sell that precise physical DVD — not unlike buying a book, blacking out various passages, and then re-selling that physical book. Anyway, they lost;

• And of course, 2011’s CCA and B v. F+W Media, which ruled that the parody book Elf Off the Shelf (featuring a drunken, naughty elf), was, indeed, legal. Thank God for that.

The Fair Use Index: really great browsing, if you’re interested in copyright!