You know, of course, of my Hierarchy of Beards poster, surely one of the most invaluable teaching materials made available to the public since the invention of the vivisection. And I have also shown how mine is merely one in a storied history of facial-hair taxonomies. Today, let us consider some others. (The images are clickable.)

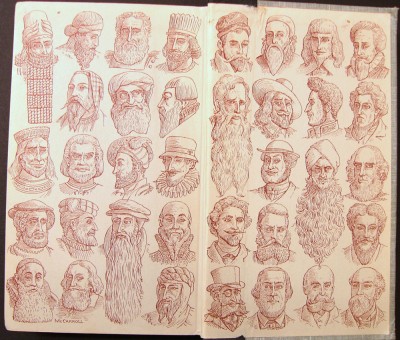

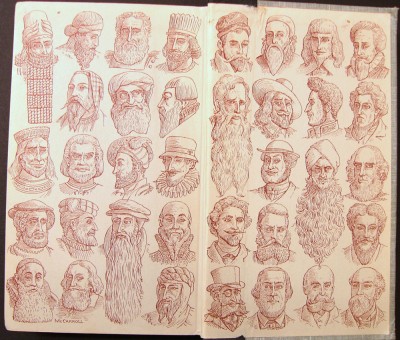

These are the endpapers from a 1949 edition of the Reginald Reynolds classic Beards: Their Social Standing, Religious Involvements, Decorative Possibilities, and Value in Offence and Defence Through the Ages, which tries its merry best to be utterly unreadable, but the 1976 American edition of which has one of the greatest covers in history.

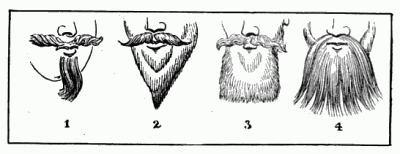

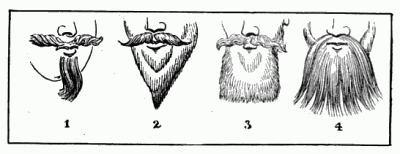

These examples are from the 1904 book At the Sign of the Barber’s Pole: Studies in Hirsute History by William Andrews, a book filled with interesting anecdotes about hair fashion throughout European history. These images are from a section about seventeenth-century beard poetry, an example of which (by John Taylor, 1580-1654) runs thusly:

“Now a Hew lines to paper I will put,

Of men’s beards strange, and variable cut,

In which there’s some that take as vain a pride

As almost in all other things beside ;

Some are reap’d most substantial like a brush,

Which makes a nat’rel wit known by the bush ;

And in my time of some men I have heard,

Whose wisdom have been only wealth and Beard ;

Many of these the proverb well doth fit,

Which says, bush natural, more hair than wit :

Some seem, as they were starched stiff and fine,

Like to the bristles of some angry swine ;

And some to set their love’s desire on edge,

Are cut and prun’d like a quickset hedge ;

Some like a spade, some like a fork, some square,

Some round, some mow’d like stubble, some stark bare ;

Some sharp, stiletto fashion, dagger-like,

That may with whisp’ring, a man’s eyes outpike ;

Some with the hammer cut, or roman T,

Their Beards extravagant, reform’d must be ;

Some with the quadrate, some triangle fashion,

Some circular, some oval in translation ;

Some perpendicular in longitude ;

Some like a thicket for their crassitude ;

That heights, depths, breadths, triform, square, oval,

round, And rules geometrical in Beards are found.”

A bit hipper and more ironic is artist Myra Mazzei’s “Mustache Chart,” which focuses specifically on many of the 20th century’s most notable lip-adornments, from Hitler to Zappa. Instead of depicting archetypal styles, in the manner of most charts of this nature, each example here portrays an individual well-known moustache in loving detail. This type of chart is useful for the connoisseur who’s more interested in the subtle variations between, say, the Selleck and the Stalin, than in ogling the outer boundaries of the form à la a fourteen-year-old reading Hot Rod magazine.

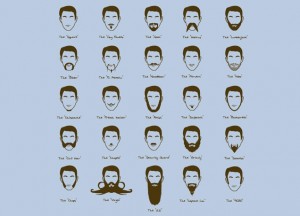

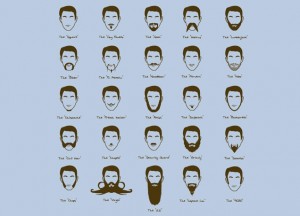

Along similar lines is this Threadless design, “Facial Hair Club for Men.”

Similar in content but somewhat more self-congratulatory for its own cleverness is this “Mario Mustache Chart,” which I haven’t been able to trace to a creator (please post a comment if you know). A clever idea but a bit too yesterbatory for my taste.

From well-known beardist Jon Dyer comes a home-grown collection of dozens of different beard configurations, and those who’ve been following the beard scene awhile know that Jon is on a mission to personally experience every different style on his very own face. A hero to many.

I should remind the reader, however, that my own beard chart goes one further and actually outlines the interrelationships between the many different classes of beard. If we are ever to push our discipline forward, there is a need for exploration and classification of more aspects than simple design — how do different beards stack up in different climates? What are their requisite levels of upkeep? And perhaps most crucially, in what manner may a man’s beard communicate telepathically with other beards? These and other frontiers of pogonology still remain to be quantified in chart form.

But for now, at least, we have this: