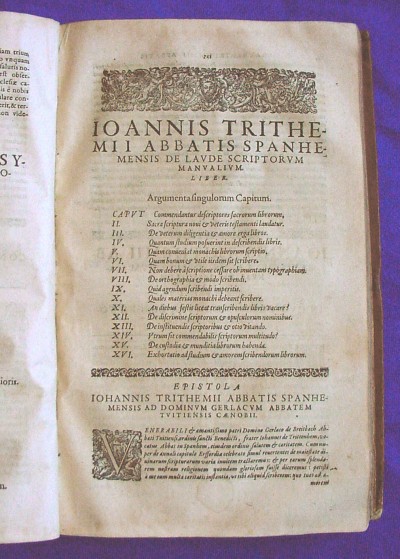

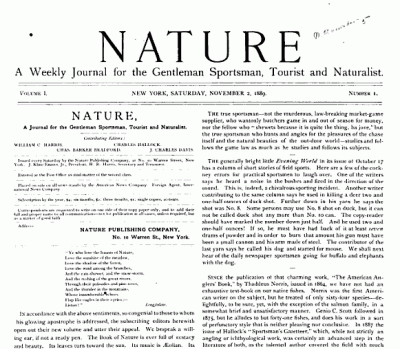

Previously, I shared a curmudgeonly 1889 article about the menace of electricity and the telephone and its spiritual cousin, a fifteenth-century screed lamenting the printing press. I’m collecting data here in service of a hypothesis that progress is universally despised, that the “get off my lawn you whippersnappers” feeling that we all occasionally experience is more tied to our makeup as humans than the technology and the changes themselves. These feelings, I posit, are universal, and perhaps make us feel disconnected — we see others doing things differently, and experiencing life in a different way, and we can’t understand it, or all we can see is what they’re missing. If only they would realize! But those people are not bad — they are simply native to the next thing, perhaps, and they experience the world slightly differently. And so the world turns.

When I mentioned that I supposed this curmudgeonly sentiment against progress was common all throughout history, some commenters pointed me to the Phaedrus, a Socratic dialogue of around 370 B.C.

In it, Socrates recounts to Phaedrus the Egyptian legend of Theuth, the god who invented “numbers and arithmetic and geometry and astronomy, also draughts and dice, and, most important of all, letters.” Theuth presents the Egyptian king Thamus with his many inventions, and Thamus

…said many things to Theuth in praise or blame of the various arts, which it would take too long to repeat; but when they came to the letters, “This invention, O king,” said Theuth, “will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memories; for it is an elixir of memory and wisdom that I have discovered.”

But Thamus replied, “Most ingenious Theuth, one man has the ability to beget arts, but the ability to judge of their usefulness or harmfulness to their users belongs to another; and now you, who are the father of letters, have been led by your affection to ascribe to them a power the opposite of that which they really possess.

“For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.” (Phaedrus 274c-275b)

To which Phaedrus calmly replies: “Socrates, you easily make up stories of Egypt or any country you please.”