Modern-day photo retouching (as in here and here) is a big business in the world of magazines and advertisements and mass media, and every now and then there’s an outcry about how fake it all is. It distorts perceptions of beauty and reality, and elevates celebrity onto weird unblemished pedestals.

Before lumping this into “a problem with our modern world” too fast, though, remember that it was always thus: kings and queens were flattered by their bust-sculptors and portrait-painters, and as soon as photography was invented, there were retouchers. Drawing onto negatives with a pencil to prompt prints to come out lighter, or delicately scratching away emulsion to prompt prints to darken, they removed stray hairs, straightened noses, and erased double chins from the very first.

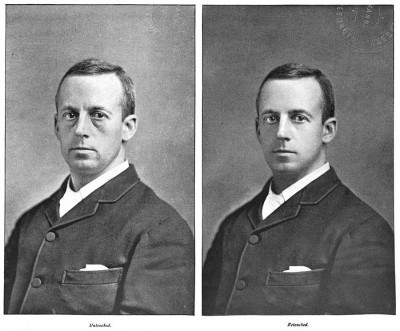

Here’s a bit from “A Magazine of Photographic Information,” March 1900 edition:

Retouching has been much condemned, alike by those who cannot practise it, and by those of artistic trend; we must admit that in many hands its use is pushed far beyond its legitimate scope, and with deplorable results. If, however, we judge a process by its abuse, then all photography must be placed under the ban, for certain it is, that many things photographic are produced which are without any merit whatsoever beyond the negative one of probable impermanence.

The article continues on to be quite prescient:

The Coming Retouching

What retouching should be, it is impossible to say. The retouching of the future is a matter of gradual evolution, rather than of demonstration. Probably the amateur will suggest it in part, but it should come more from the steady worker who day by day steadily pencils over his pile of negatives. It may safely be said that, far from being superseded, retouching, in a modified form, will be more universal in the future than in the past. Possibly it will often be nearer “faking” than retouching, but there will be few pictures, save those of beginners, which will be “straight prints from straight negatives.”

Here’s a bit from the 1898 book Amateur Portraiture at Home, which realizes it has to dip into the subject of retouching, but sure isn’t happy about it:

To be frank, I hate to say one single word on this subject, and yet, if I may judge from my correspondence, it is one in which most amateurs would appear to be keenly interested. One and all would seem to think that it is a cure for all photographic ills, and that if they could retouch they would forever be able to turn out fine work.

There never was a greater delusion. Retouching, properly used, is a great aid in photography, but with the majority of photographers — whether amateur or professional — it is looked upon as a handy means of remedying poorly lit, wrongly timed or badly developed negatives, and not infrequently a combination of all three. With such individuals retouching means working with a pencil over every part of a face until the original texture is entirely obliterated, and then they proudly view the result as a work of art.

My own experience of professional retouchers has been most unsatisfactory. No matter how much I instruct them that all I want done is the removal of technical blemishes, they seem to think that unless they put a new skin on the sitter they have not earned their money. To me this is simply maddening, for I am simple enough to hold the opinion that the one thing in which photography excels is the rendering of texture, and that the man does not live who can come within a thousand miles of the camera in that respect. Now, the human skin is a wonderful bit of work, and the greatest painters spend a lifetime in a vain effort to be able merely to suggest it. So when I see a man priding himself on being a first-class retoucher, because in a few minutes he can simply annihilate the marvelous work of the lens, I feel he is so small mentally that I ought to consider him as nonexistent.

I think I have said enough to impress on the reader the idea that every stroke of the pencil on a negative is more apt to be productive of evil than good, and that the only legitimate occasion for retouching is to correct such technical defects as pin holes caused by dust or airbells, or to remove such natural blemishes as freckles, which are often invisible to the eye, but are rendered very distinct in the photograph, on account of photography being a defective art so far as the rendering of colors is concerned.

And speaking of colors, reminds me that young people with rosy cheeks are apt to be treated rather unkindly by the camera, for this fine, healthy tint is rendered dark and suggestive of a shadow indicating a hollow, when the condition is actually the reverse. This, of course, must be remedied; but when the face is properly lit, as is laid down in the first and second chapters of this book, it is surprising how correctly the qualities of tone are rendered.

So-called first-class retouchers pride themselves in being able to retouch three and four negatives in an hour, but I am acquainted with men who are really masters of lighting, who can do all they want on thirty negatives in the same period of time and not hurry themselves at that. The moral is that the so called first-class retouchers have to patch up the poor work of second-class operators, and there is no earthly reason why the student of this little book should belong to the latter class.

But in this 1895 book, Photography, Artistic and Scientific, author Robert Johnson plays my own game: reminding critics that even what they hold dear, someone before them once objected to:

On the subject of retouching photographic negatives, there are a great many conflicting opinions, and a great deal of nonsense has been uttered both for and against this operation; some perfectly competent photographers urging that a photograph is quite incomplete until it has been retouched, others asserting that when a negative leaves the dark room it is quite ready for the printer; that it is bad taste, bad art, and, in fact, a very objectionable thing to interfere with it in any way. […]

Retouchers have only themselves to thank for this attitude taken against them. Some retouching is detestable; it is senseless and purposeless, and cannot be too much condemned. But as there are artists and Artists, photographers and Photographers, so there are retouchers and Retouchers; and we may assume that if the object of retouching be legitimate, and if it be carried out in a discreet and intelligent manner, the result should justify the process. It is most probable that any very sweeping condemnation is inaccurate, so, on the other hand, blind partisanship of any process or theory is likely to lead us astray.

It is not so very long ago that photography itself was condemned in a most wholesale manner. A photograph, it was said, could not be a work of art at all; it was purely mechanical, and had no claim to be considered as artistic. The photographer was understood to be a somewhat dirty individual, arrayed in a velvet coat and a slouch hat, whose fingers were generally black with nitrate of silver.

We have been nauseated with the silly discussions that have been held about his claim to be considered as an artist. We have lived through this — “the old order changeth, giving place to the new” — and the intelligent painter has recognized that photography, while it cannot rival, can teach him, and that while he cannot by his sneers injure an art which has its base in truth, that very art may draw attention to his own shortcomings. He is fortunate if he be the first to notice and correct them.

This is all passed, and painters, sculptors, in fact, artists of almost every type, have admitted that certain photographs have fully justified their claim to be considered “works of art.” This is as it should be. It is a narrow and bigoted perception that can only see one side of a subject, and we think that if we keep our minds open on the subject of “retouching” a photograph, we shall conclude that it is not only justifiable, but necessary, on artistic grounds. […]

If we have come to the conclusion that a certain pose and lighting is best adapted to one particular head and face, it may be found that this is attended with a small defect, such, for example, as too deep a shadow under the eyebrows, or the cheekbone may be too marked, some small peculiarity of feature may be emphasized — something we should not observe in the ordinary way. It cannot be incorrect to remove these defects; it is better to do so, and retain the great advantage of the most suitable pose and lighting, rather than to sacrifice these in order that the small defects that accompany them may disappear without other aid.

As to the temporary blemishes that sometimes exist, such as freckles, pimples, patches of colour on the sides of the nose caused by the pressure of a pince-nez, it is very difficult to see by what process of reasoning we are to consider them as essential to the artistic fidelity of a portrait. Freckles are brown, the other defects are generally red; and as they can be seen on the developed negative as marks of too great transparency, they will print simply as darkness. A sculptor does not attempt to reproduce them; he knows how futile such an attempt would be.

All intelligent photographers are aware of the limitations of their art; they know that, whatever may be alleged to the contrary, photography in colour is not yet an accomplished fact; they know, or should know, that the inability to reproduce the equivalent value of colour is an inherent defect of photography.

But in condemning retouching which is only senseless stippling for the direct purpose of making all faces alike, of bringing them all to one standard of smoothness and roundness, we most heartily join. But that judicious retouching is a very great advantage we have no doubt whatever; it is an absolute necessity, in our opinion, in order to obtain the best result, which is admittedly the object of all art. The commercial advantage of it we do not press, because even the most bigoted of its enemies do not dispute that. An experience of many years with the highest class of professional work has taught us that it is simply indispensable if one would obtain any pecuniary advantage in the practice of portraiture.

He goes on to shout at length about where to buy the right kind of glasses for the delicate work of retouching, and then advises: “Let your desk stand in front of a window with a north light if possible, as it is least variable; let it be inclined towards the window at an angle of about 80° with the horizontal, and let the space through which the reflector is looked at be at such a height that your eyes are directed in a line at an angle not greater than 30º with the level of the table at which you sit. If this angle be greater you would have to look down upon the negative, which would make the head ache, apart from the light not being so good. The position of the body should be upright, with the head leaning just the least bit forward, enabling you to slightly alter the distance between the eyes and the negative without moving much in your seat; this movement is necessary in order to see what you are doing.”

And there are pages and pages more of this. I picture folks agreeing with him thusly:

“ROBERT FINE YOU WIN YOU WIN IF YOU WILL JUST BE QUIET”

This topic continues: True Stuff: Idealized vs. Realistic Portraiture

Oh man, I find it fascinating that the same arguments haven’t changed in over a hundred years, and that the language is almost the same in these books as the arguments that go on over Flickr and other forums nowadays. Thanks for sharing!

…never to mention the official pictures of Gorbachev, which always omitted the rather enormous birth mark.

The morality of retouching aside I always find it absolutely hilarious when the people doing the retouching have no concept of anatomy and make the celebrities on magazine covers look like freaky almost human aliens with squashed heads, mutated limbs, and other oddities. The thought that someone higher up in their company okayed their shoddy work makes me laugh and cry at the same time.

And here I was, wondering why some old pictures look unreal and such…

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose…

Interesting entry in the Plus ça change… category.

Thx.

Well argued and summarized. True Stuff indeed. It is interesting looking into how people define and consider “blurry” things like art, and how that changes throughout time (and it is always LOLable to see how they can bicker over its definition)

Interesting counterpoint: there was an entire industry of photographers who sold “painted photographic” portraiture. Say a family wanted a portrait done but couldn’t afford a painting (a sign of wealth and class). They’d commission a photographer to take a photograph of the family, and then have him paint over the image to make it look more “painterly”, thus giving them better social airs. Different side to the act of retouching.

For those interested, a PSU professor specializing in the art and history of photography wrote about the painted photographs they found in flea markets and thrift shops in Central PA (book here – http://amzn.to/gOqcwJ).

Stephany: While it may be true that the arguments against retouching haven’t significantly changed, I find it highly unlikely that the modern arguments include conclusions as awesome as the one presented in this post. “Retouching is for photographers that suck” doesn’t have the same ring to it.

The same arguments have developed in music production nowadays with nonlinear digital editing and, especially, with autotune. I loved that line where he talks about how they annihilate all the texture that the lens is capable of capturing. Mic’ing is photography, one of my old teachers used to say..

The same arguments have developed in music production nowadays with nonlinear digital editing and, especially, with autotune. I loved that line where he talks about how they annihilate all the texture that the lens is capable of capturing. Mic’ing is photography, one of my old teachers used to say..

I wonder what they would have thought on the subject of coloring photos before color film was widely available? I own a picture of my family (my mom and dad, we five kids, and my oldest sister’s 18 month old daughter that was taken when I was three, and it was hand-colored (I also have the original black and white version). Whoever did the coloring did an excellent job, my mother told me once, as far as capturing not just the color of the clothing, but also the color of hair and eyes.

Color film WAS available to the general public, but in our case, the cost was prohibitive; it was actually cheaper to have the picture taking by a professional, then hand-colored.

It never occurred to me to wonder if he retouched it as well.