The 1894 book Revolted Woman: Past, Present, and to Come by Charles George Harper is hideously, horrendously sexist. It starts off right away, fearfully mocking the very notion of equality:

She is upon us, the Emancipated Woman. Privileges once the exclusive rights of Man are now accorded her without question, and, clad in Rational Dress, she is preparing to leap the few remaining barriers of convention. Her last advances have been swift and undisguised, and she feels her position at length strong enough to warrant the proclamation that she does not merely claim equal rights with man, but intends to rule him.

Such symbols of independence as latch-keys and loose language are already hers; she may smoke — and does; and if she does not presently begin to wear trousers upon the streets — what some decently ambiguous writer calls bifurcated continuations! — we shall assume that the only reason for the abstention will be that womankind are, generally speaking, knock-kneed, and are unwilling to discover the fact to a censorious world which has a singular prejudice in favour of symmetrical legs.

Right out the gate. Page 1. Wow!

I will spare you hundreds and hundreds of pages of misogyny (spoiler alert: woman “has ever been the immoral sex”; “has ever been the active cause of sin”; &c. &c.) but will point out this bit, in service of my active hypothesis that everything is always the same, ever:

Directly a woman marries, she considers that she has full licence; although, goodness knows! the unmarried girls of to-day are latitudinarian enough, and do, unreproved, things that thirty years ago would have branded them with an ineffaceable mark of shame.

“Back in my day, things were fine. But these kids today…!” Every generation, from 1894 — heck, from 1894 B.C. — till today has always felt that the kids now are worse than ever before, a disgrace to society, and overall a shameful, worthless generation.

That said, while Mr. Harper’s good-old-days curmudgeonliness may not be uncommon today, I am quite happy that the particulars of his objections are by modern standards laughable. What do the women of to-day do to earn the scornful label “latitudinarian”? Why:

• “She aspires to be the boon companion of the men; she plays billiards with the manly cue, and not infrequently she can give the average male billiard-player points, and then beat him.”

• “She has not annexed the cigar and the pipe yet — not because she lacks the will, but her physique is not yet equal to them; but she can roll a cigarette, can take or offer a light with the most practised and inveterate smoker who ever bought a packet of Bird’s Eye or Honey Dew, and she wears — think of it, O Mrs. Grundy, if, indeed, you are not dead! — a smoking-jacket.”

• “Slang and swearing are the commonest — in two senses — accompaniments and underlinings of the smart woman’s speech: any little disappointment that would have been ‘annoying’ to her mother is to the modern and up-to-date woman a ‘condemned nuisance,’ if not more than that; and ‘damns’ fall as readily from her lips as the mild ‘dear me!’ of a generation ago.”

• “Woman does not date her correspondence. She has no ‘views’ on the subject; she simply forgets. Sometimes, indeed, she will head her letters with the day of the week; but, as the weeks slip by, a letter written on any ‘Wednesday’ becomes rather vague in date. Also, it is notorious that the gist of a woman’s letter, the real reason of its being written, appears in a postscript.”

• “At present she carries her purse in her hand along the most crowded streets, at the imminent risk of its being snatched away. Ask her why she does this, and she will tell you that she has no pockets, or that they are difficult to reach, or else that they are too easily reached by pickpockets. It never occurs to her that the devising of new pockets comes within the range of the dressmaker’s craft. Not that it matters much; for the purse-snatcher obtains little result for his pains, and, beyond some postage — stamps, half a dozen visiting-cards, a packet of needles, and a few coppers, his enterprise usually goes unrewarded.”

Finally and most distressingly:

• “Women…may exercise their brains and their muscles to their utmost tension; but let them not in those cases exercise the natural function of woman and bring children into the world. For nature, which never contemplated the production of a learned or a muscular woman, will be revenged upon her offspring, and the New Woman, if a mother at all, will be the mother of a New Man, as different, indeed, from the present race as possible…But it is not to be supposed that even the prospect of peopling the world with stunted and hydrocephalic children will deter the modern woman from her path, even though her modernity lead to the degradation and ultimate extinction of the race.”

Let me repeat that argument: If women get too bent off their ‘natural’ ways, they’re going to have deformed children and the human race will perish. All this and I’m only up to page 27 of this book.

I’m actually quite glad that this reads as hilarious — because it means that society has come a long way from this sort of argument being commonplace. At least, that is, with respect to sexism. Pointing out the “obvious”, appealing to “nature”, and endless “but think of the good of society!” pseudo-logical rationalizations have been, and sadly continue to be, the same whether the argument addresses sex, race, religion or sexual orientation. And they all seem to stem from a fear of losing power.

I have found countless articles and books of this era that address the relationship between the sexes in terms just as derisive as this, and some of the more boisterous ones such as Revolted Woman can be funny in their cocksure, utterly misled conviction, but when the same arguments are mapped onto present-day struggles, the text becomes somewhat less fun to read, less easy to laugh at. So I will skip ahead a hundred pages or so to the descriptions of

Conjugal Duels

In a chapter headed “Domestic Strife,” in which he (surprise!) exhorts men to rule absolutely over their wives, Harper gives examples of marital struggles through the ages. A medieval French poem tells of a couple fighting bloody tooth and nail over a pair of breeches; an English woman locks her husband in a window-shade as if it were a pillory. And then this, from a 15th-century German manuscript:

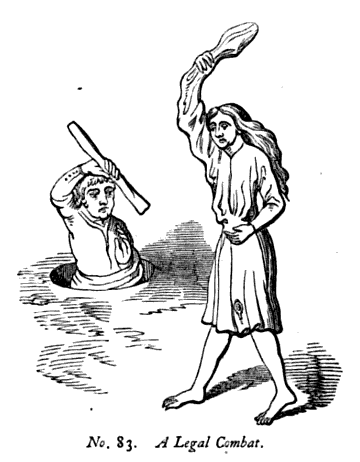

In Germany, during mediaeval times, domestic differences were settled by judicial duels between man and wife, and a regular code for their proper conduct was observed. ‘The woman must be so prepared,’ so the instructions run, ‘that a sleeve of her chemise extend a small ell beyond her hand like a little sack: there indeed is put a stone weighing iii pounds; and she has nothing else but her chemise, and that is bound together between the legs with a lace. Then the man makes himself ready in the pit over against his wife. He is buried therein up to the girdle, and one hand is bound at the elbow to the side.’

Another reference to this strange practice is found in A History of Caricature and Grotesque (1875), adding more details to the scene:

At this time the practice of such combats in Germany seems to have been long known, for it is stated that in the year 1200 a man and his wife fought under the sanction of the civic authorities at Bale, in Switzerland. In a picture of a combat between man and wife, from a manuscript resembling that of Paulus Kall, but executed nearly a century later, the man is placed in a tub instead of a pit, with his left arm tied to his side as before, and his right holding a short heavy staff; while the woman is dressed, and not stripped to the chemise, as in the former case. The man appears to be holding the stick in such a manner that the sling in which the stone was contained would twist round it, and the woman would thus be at the mercy of her opponent.

In an ancient manuscript on the science of defence in the library at Gotha, the man in the tub is represented as the conqueror of his wife, having thus dragged her head-foremost into the tub, where she appears with her legs kicking up in the air.

This was the orthodox mode of combat between man and wife, but it was sometimes practised under more sanguinary forms. In one picture given from these old books on the science of defence by the writer of the paper on the subject in the Archæologia, the two combatants, naked down to the waist, are represented fighting with sharp knives, and inflicting upon each other’s bodies frightful gashes.

(The journal Archæologia [Volume 29, from 1842] does indeed contain what appears to be the original description of the A.D. 1400 manuscript that the other accounts quote and cite.)

So what have we learned? Women’s emancipation has come a long way: marital conflicts are regrettably no longer resolved by the wife donning a chemise with a sling full of rocks attached and the husband waving a stick around while standing in a pit. Oh, those ‘good old days’!

UPDATE: From the comments: “If you want more info on the rather bizarre judicial duel between man and woman, it’s depicted in detail in Hans Talhoffer’s Fechtbuch from 1467 (plates 242-250). The plates / English translation”

AMAZING