The late nineteenth century was full of daredevils, fame-seekers, and people doing absurd things for the sake of doing absurd things. Mass communication was new, and could bring nationwide notoriety to anyone able to break some barrier or accomplish something no one else had. The age of the media-savvy showman had dawned.

What did “Paul” (a pseudonym) claim he would do? Walk around the Earth, starting without a penny to his name and completely nude, and promising to end a richer man than he began. It’s a strange story of completely manufactured celebrity. From the article linked above:

GLOBE-TROTTING is now so common that no one pays much attention to any plan of putting “a girdle roundabout the earth” unless that plan possesses daring originality impossible of execution. The plan of Mr. “Paul Jones,” who recently became the most-talked-of man in Boston, the “Hub of the Universe,” fulfilled the two requirements. It certainly was daringly original, and the chances seemed dead against its accomplishment. Moreover, the fact that Mr. “Paul Jones” was, owing to the nature of the plan, forced to hide his identity under an assumed name, lent a lustre to the exploit that clinched public attention at the outset.

The plan, in short, was as follows: “Jones” had made a wager that he would start out on a trip around the world as Nature made him — that is, naked. He guaranteed that he would make the trip in a year, starting without a penny in the world, and without begging or borrowing on the way. He also stipulated that he would make five thousand dollars (£1,000) during the trip, although he was not compelled to bring that amount back with him. If he won he was to get £1,000, and if he lost he was to pay that amount. The minor details of the wager were completely overshadowed, however, by the first clause in the agreement, which made it imperative that he should start out in the “altogether.” How would he do it, and wouldn’t he be arrested? These were some of the questions that were asked.

But the man who made the wager had a surprise in store. A Monday night was appointed for the start, and the Boston Press Club, which had taken a keen interest in “Jones,” offered its rooms for the occasion.

At the appointed time, Jones found himself the centre of a large gathering of newspaper men, sports, men about town, politicians, and others interested. As the moment approached when he was to make the start, the interest grew intense. A committee took him into a private room, removed all money from his person, and Jones, himself, quickly stripped. A placard was now placed on the door as follows:—

PAUL JONES

STARTS FROM THIS ROOM.

ADMISSION ONE CENT.

Of course, the fee was quickly paid, and the tall, athletic frame of a handsome man dressed on the Garden of Eden plan was now visible to the spectators.

The crowd wondered what Jones would do next. They did not wait long in suspense. With the money that had been taken at the door, Jones sent out a paid messenger for some wrapping-paper and pins. The wrapping-paper soon came in, and with a big pair of scissors the ingenious man set to work. A few deft movements of the scissors, and the paper began to assume the form of trousers. The legs of these were joined together with pins. Then a covering for the waist was quickly made, and a sort of cape to cover the shoulders. The progress of the work was followed with immense interest, and the spectators were lost in amazement at the cleverness and rapidity with which the man worked.

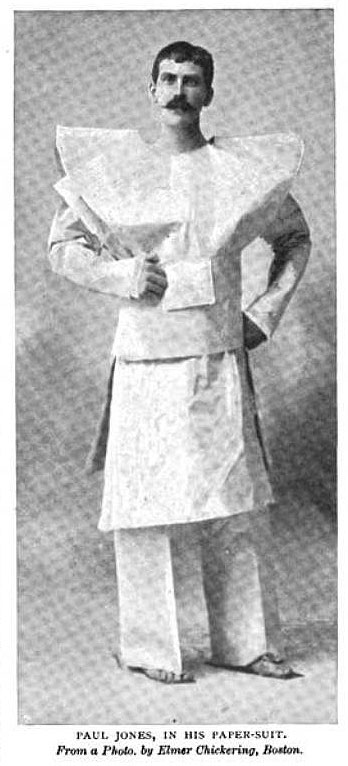

In the illustration on this page we see him as he stood before the Press Club and its guests — a paper man, without a penny to his name, except those which, in a few short minutes, he had collected by the exercise of his mother wit.

At the end of the first evening Jones was two pounds richer than when he began. He sang an original song, and a small admission fee was charged to hear it. He also made copies of the song and sold them to the Pressmen and others who would buy. He sold his autographs for five cents apiece. He also let the spectators feel his muscle, for a nominal sum, and offered to spar anybody for a stake. Nobody, however, accepted. He had several offers for his paper-suit, but would accept none of them. The clever man knew that when the morning papers came out with the account of the previous night’s doings, that suit would have a money value far in advance of the prices offered. So, in his paper-suit, he went out to one of the best hotels — and went to bed.

The next morning everybody in the city knew of Jones’s feat. He spent the early part of the day in making a new suit out of blankets which he had bought from the proceeds of the previous night. This suit served a temporary need for warmth, as it was a cold winter’s day, and, as one may see from the illustration, the suit was somewhat like pyjamas. As yet, Jones had no shoes. The night before he had hastily manufactured a pair of sandals out of two pieces of purchased leather, and these he wore until he had collected money enough to buy some shoes. The purchase of the blankets left him 5 1/2d. short on his breakfast, but a reporter gave this to him for an interview. He now struck the proprietor of the hotel for a job, and got a dollar for one hour’s work. For carrying placards on his back advertising the hotel restaurant he got £2. Thus his morning’s work brought him in 44s.

A clothing-house now came to the front with an offer of £2 for the papersuit, which they prominently exhibited in their window. They also hired him as salesman for the afternoon —- a coup that attracted a large number of people into the shop to see the man in the blanket-suit. The autograph business still went on with profit, and with the proceeds Jones bought a large quantity of new and shiny cents, which he sold as souvenirs at a fancy price. He paid for his supper by working forty minutes as a waiter in a restaurant, and everywhere he went in his blankets, he was followed by large crowds.

After supper he added materially to his store by inviting people to a “smoker” in the hotel. It cost nothing to get in, but lots to remain. To sit on the bed for five minutes cost a halfpenny. A chair was let at the rate of a halfpenny a minute, and standing-room was sold for a halfpenny per half-hour. The crowd was large and enthusiastic, so Jones bought a box of cigars and liberally passed them round. No one, however, was allowed to expectorate without paying a halfpenny! This brought in a large profit. Jones now announced that he would sing his original song at 2 1/2d. per head. The audience then unanimously and gratuitously paid him a like amount to quit. At the end of the evening Jones was £20 to the good.

The next day he made preparations for leaving Boston. His plan was to visit several of the Eastern cities, which, through the Press reports, had already been apprised of his wager and the remarkable events of the first two days, and, in these cities, collect enough money to buy a steamship ticket to the Old World. He expected little success in Europe, but would push on steadily to the East, and when he arrived in San Francisco, would begin a lecturing tour in all the principal cities of the United States. Already, indeed, offers for lectures were pouring in upon him. Commercial houses, also, made arrangements with him to advertise them on tour, and to peddle their wares. For this he was promised astonishing sums, and on the second day his thousand pounds were assured.

But before he left Boston he bought a good suit of clothes and a necktie out of the proceeds of the previous day. The remainder he put in the bank. He got shaved, paid £1 for a pair of shoes, and 30s. for an overcoat. He made his breakfast by shining an admirer’s boots, and this gave him the idea of hiring a bootblack’s outfit for a few hours, by which means he made a good sum quickly. Previously he had had photographs of himself taken in his three suits. These he sold at good prices in the various cities he visited. He regularly charged 2 1/2d. for a hand-shake, and thus loaded his pockets with loose “nickels.”

The first city he visited, after leaving Boston, was Providence. He arrived in his quadruple capacity as travelling salesman, advance agent, lecturer, and “globe-trotter.” The Providence Press Club entertained him, and he entertained them by repeating his Boston experiences. In the evening he was advertised to appear at the Pawtucket Opera House, to be examined by a mind-reader. The house was crowded. He had also made an engagement to appear in Boston the same evening, and to get to Boston in time, he was compelled to hire a special train. He appeared on the stage promptly, before an overflowing audience, and made a speech, for which he was paid, it is said, £30. He also sang his song and gave an exhibition of sawing wood. […]

From Providence he went to Springfield, and here repeated his success. He gave a lecture to a large crowd, sang his song, and sawed wood. An enterprising haberdasher hired him to tend in a shop for an afternoon, and a chemist drew a large trade by getting him to stand at a soda-fountain, draw fruit syrups and lemonade, and sell cigars and tobacco. One of his customers was a police-inspector who had come to arrest him for the non-payment of a debt contracted in Boston before he made the wager. This debt Jones paid. Two days after a claim for £10 was made against him by a firm which had secured him a position as teacher in a Massachusetts town. Another claim for £17 was later produced. Jones paid neither claim, and was locked up. The newspapers then investigated the whole affair, and found that “Jones’s” real name was Pfeiffer, that he had had a college education, and that, being in hard straits, he had invented the story of a wager, and had hoodwinked the Press into giving it publicity. His success was enormous, but short. Strange to say, also, the very people who had become tired of the name of “Paul Jones” were the first ones to express sorrow over his untimely end.

To summarize: E.C. Pfeiffer, Harvard graduate, fabricated a $5,000 wager, stripped naked and offered gapes for a penny, sang songs and figured out how to be paid both to start and to stop, became a celebrity who could sell the clothes from his back and pennies from his pocket…and then ended up in a debtor’s prison. It was a whirlwind two weeks in which he dominated the Boston press.